Looking back to the very first installment to my Oil, Rockets and Feathers mini-series more than 2 months ago, I hadn’t expected that I would have materials to discuss on, spanning 4 individual articles.

But if there was anything I had learnt from embarking on this little writing adventure, it was that:

- This is a heated topic in Singapore that probably will never go away; and

- I am definitely scratching only the surface – in fact I struggle to keep the articles short.

So there is much to discuss on. But if now you are thinking that I will end this mini-series with a bang, be prepared to be disappointed.

If you hadn’t caught on by now, the key reason behind why the topic of retail petrol prices in Singapore resembles “Days of Our Lives“, is because of the pricing opacity of petrol retailers and the perceived lack of needed government intervention.

For the benefit of younger readers (yes I feel old), “Days of Our Lives” is a still ongoing soap opera running since 1965.

So what I will write next probably won’t blow your mind. But if you stick around, even showing you why might prove useful.

There are other cost components to retail petrol.

Seriously – this surely goes down as the most underwhelming explanation because:

- It sounds like a most obvious answer.

- It says nothing much beyond (i.e. doesn’t indict the evil petrol retailers!)

Perhaps as a result, we have a strange situation of level-headed observers repeating themselves (like Chris Tan from the Straits Times here and here). And yet similar questions about whether petrol retailers are conspiring against Singaporeans (how dare they) appear year after year.

To rub salt into wound, petrol retailers do not ordinarily share their costing basis publicly because they don’t need to, and also because keeping your cards close to your chest is a key element to market competition.

After all, which part of “competitive market” necessarily spells “transparent pricing”?

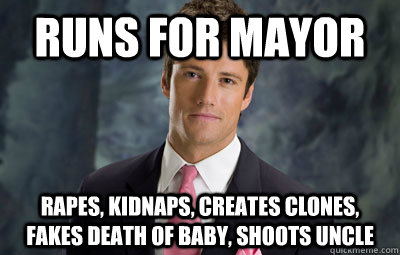

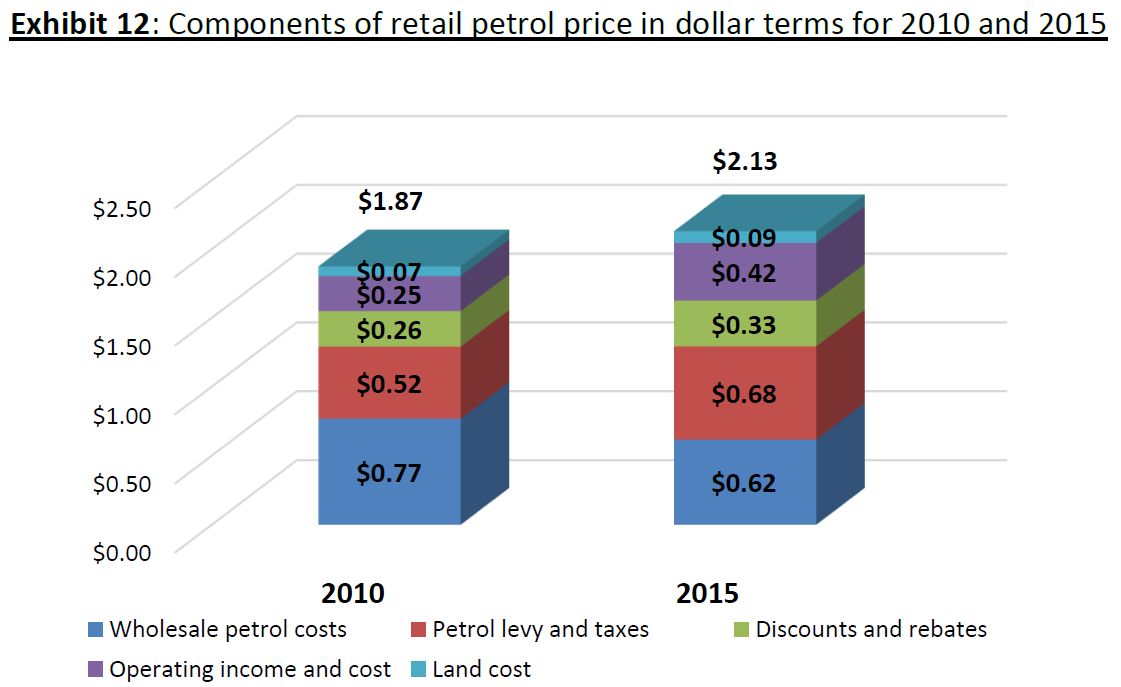

Which makes the CCCS report, which I have referenced heavily in this mini-series, and a must-read for those who are keen to know more, all the more interesting due to the following charts:

Surprise surprise – the wholesale price of petrol (i.e. the cost price of petrol from the immediate upstream) doesn’t make up even close to half of the retail price.

In fact between 2010 and 2015, the share of wholesale petrol cost fell to less than a third of petrol price. And of the average listed petrol price of $2.13 per litre in 2015, $1.51 was attributed to other cost components, of which the petrol tax and GST combined was represented by a whopping $0.62.

What this suggests is that, ceteris paribus, with a hypothetical situation of wholesale petrol costing zilch, the price of petrol will not fall below $1.51, even if the petrol retailer passes 100% of the cost reduction to the consumer.

Of course, this is highly simplistic – in reality, ceteris paribus is almost guaranteed never to hold because:

- The analysis was done in 2015 – 5 years is a long-enough time for change to happen. And going with the trend of general inflation as an assumption, it is likely that this “base” cost would now be higher.

- Petrol-retailers are profit-maximising – who’s to blame them for trying to pad revenue when they can?

The dynamic nature of retail petrol pricing.

Taking a closer look at the price components of petrol (ordered by share size):

- Petrol levy and tax ($0.68)

- Wholesale petrol cost ($0.62)

- Operating income and cost ($0.42)

- Discounts and rebates ($0.33)

- Land cost ($0.09)

Of these components, the key variables that are clearly within the petrol retailer’s control are the operating income (i.e. gross profit), and discount and rebates. Obviously it can be expected that these components can (and will) be adjusted when the wholesale petrol cost adjusts.

Movements to these components can be assumed to have strategic considerations:

- Given upstream integration of the petrol retailers, when crude oil prices fall, petrol retailers may not reduce their price as much, in order to cross-subsidise and compensate for revenue across the business group.

- When crude oil prices rise, petrol retailers may not increase their price as much, as they need to stay competitive, and also because the upstream business unit may in turn cross-subsidise and compensate accordingly.

I must be clear that these considerations are simplistic and obviously non-exhaustive – but my point should be clearly illustrated nonetheless.

That is, the price transmission between wholesale petrol and retail petrol is unlikely to be perfect because of these considerations, and the discretionary use of operating income and rebate/discount components to achieve desired revenue outcomes.

Special mention about petrol tax.

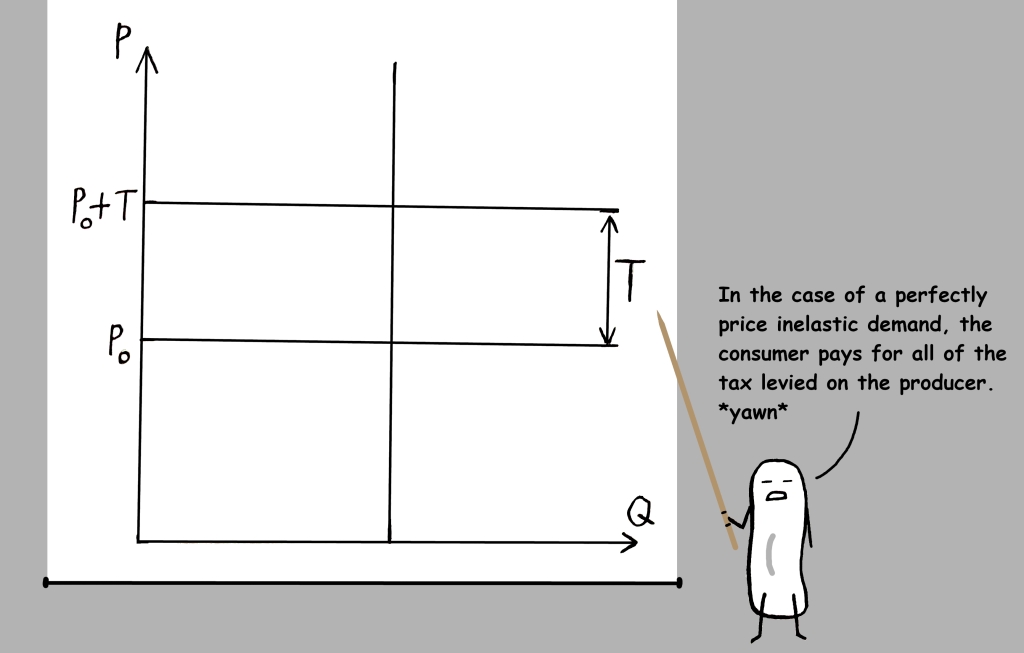

There are many who assume that the excise petrol tax is levied directly on consumers. This is not actually the case.

Unlike GST (which is included in the petrol price here), the excise petrol tax is actually levied on the petrol retailer. But due to the strongly price inelastic nature of petrol demand, and limited competition, it can be assumed that the petrol retailer will pass on almost all of the tax to consumers.

Given that the excise petrol tax rate is $0.64 for RON 97 and $0.56 for RON 92 / 95 petrol, and taking into consideration that the prevailing GST rate is 7%, we can calculate that the petrol retailers indeed pass on the excise petrol tax almost in entirety.

Taking the lower band of the excise tax rate of $0.56, and assuming that it is passed entirely on the consumer, the price of petrol (without GST) would be $2.01. Applying a GST rate of 7% yields a final price of $2.15, which is a slight over-estimation despite the conservative approach I had taken in applying the excise tax rate.

This slight discrepancy suggests a small degree of discretionary pricing by the petrol retailer in relation to the petrol excise tax, which ties in with the fact that the excise petrol tax is levied on the petrol retailer, rather than on consumers directly.

The petrol tax component (less the GST component) can therefore theoretically contribute to the imperfect price transmission we have observed in petrol prices. But it is unlikely to happen in reality, as petrol retailers tend to pass on such costs almost entirely to consumers.

Why CCCS hadn’t taken action yet.

Because they hadn’t exhibited clear anti-competitive or collusive behaviour, which would have been red flags for CCCS – you can read more about CCCS’ mandate here.

The key complaints about the retail petrol industry in Singapore are typically:

- “Suspiciously” high prices.

- Lack of disclosure over pricing basis.

These complaints by themselves are not sound basis for CCCS’ intervention as its key concern is in ensuring that firms do not engage in unfair competition.

If anything, the market inquiry conducted by CCCS indicated no sign of collusive behaviour – which has been borne out empirically on a few brief occasions where some petrol retailers deviated in pricing from the petrol retailer flock.

But it wasn’t like CCCS found that all things were exactly well.

Comparing between 2010 and 2015 in the report, the share of retail petrol price associated with operating income / cost, and discount / rebate had increased from 14% and 14%, to 20% and 16% respectively.

While operating income and cost are not reported separately for sensitivity reasons, we can’t discount the possibility of higher profit margins, especially when we observe a greater share in discount / rebate pricing at the same time, which is also purely discretionary.

So the greater pricing discretion afforded to petrol retailers signs point to limited competition (which is not the same as cooperative pricing which would have been illegal).

But should we be surprised? Of course not – the market for retail petrol is oligopolistic due to the small size of domestic demand, coupled with high barriers to entry. Hallmarks to such markets include inflated, but sticky prices, which have been confirmed by CCCS’ report.

So short of overt government intervention, the basis of which I would not comment here, we can expect the complaints about “Oil, Rockets and Feathers” to persist, and the government’s response to stay muted, in the grand scheme of things.

And it’s a wrap!

If you have enjoyed reading my articles, why not share it with others, or leave a comment below to interact with me?

Hit subscribe here to get my articles straight to your inbox hot and fresh!

Admiring the hard work you put into your blog and detailed information you

offer. It’s great to come across a blog every once in a while that isn’t the same unwanted rehashed material.

Great read! I’ve saved your site and I’m including your RSS feeds to my Google

account.

LikeLike

I really like and appreciate your article.Really looking forward to read more. Much obliged.

LikeLike