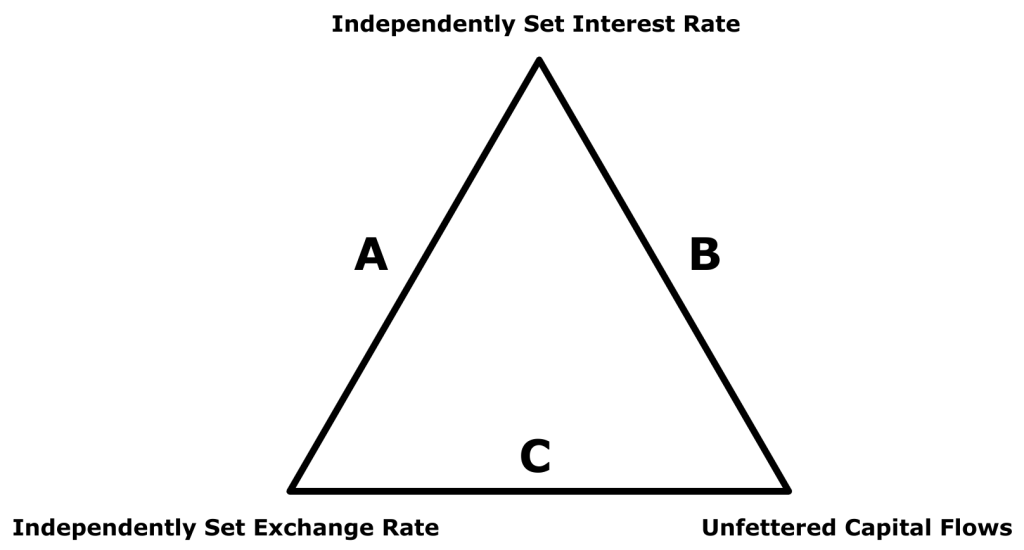

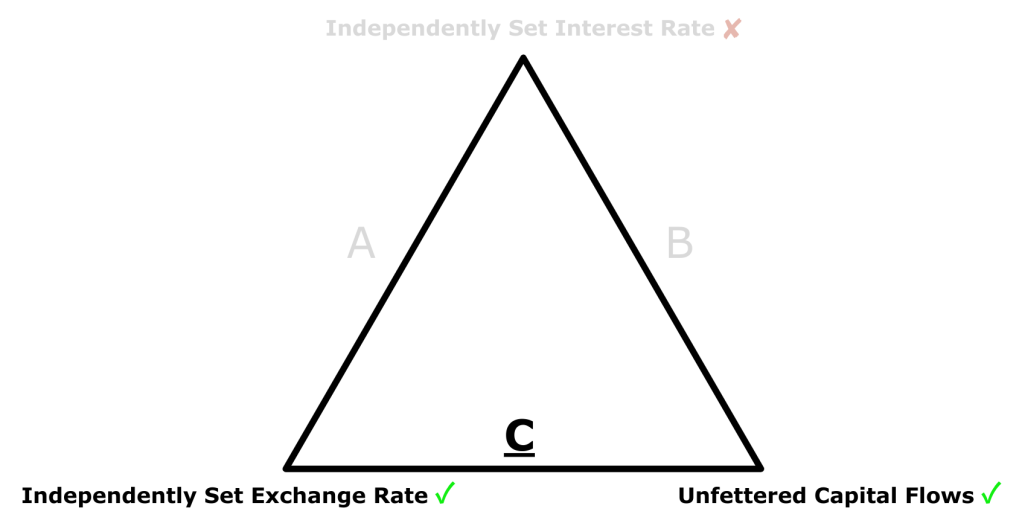

The Impossible Trinity is a concept in International (Financial) Economics with a key assertion that no economy can achieve all 3 of the following economic states simultaneously:

- Independently set interest rate;

- Independently set exchange rate; and

- Unfettered capital in/outflows.

The following discussion isn’t an explicit requirement for “A” level Economics. However, time and again, the exam questions have required at least implicit knowledge of the Impossible Trinity, especially to the question of why Singapore doesn’t pursue interest rates as a means for its monetary policy.

Constructing the Trilemma.

It should be fairly obvious that if we represent each of these states as a point on a polygon, you will get a triangle (because 3 states = 3 points).

Per the assertion of the Impossible Trinity, economies can be expected to abide to one side of the triangle only (i.e. A/B/C).

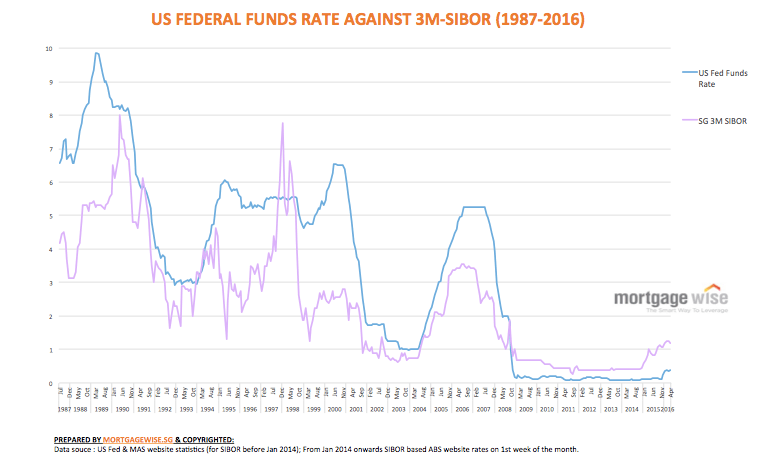

For example, in the case of Singapore, its economic policy can be characterised by Side C, as it doesn’t actively manipulate its interest rate.

As you can see in the chart above, the SIBOR (Singapore Interbank Offered Rates), which is the reference interest rate for Singapore, closely tracks the prevailing US Fed Funds interest rate.

More on that later, but first…

Assumptions.

Before questions pertaining what-ifs and how-abouts stream in, I should put across explicitly that the Impossible Trinity seeks to answer the question of how an open economy may maximise monetary control options.

Simply put, there are 2 important pre-requisites to ensure that the following discussion will make sense:

- The monetary authority must have at least a monetary policy, be it relating to exchange rate or interest rate manipulation. Without one, we may as well not start this discussion!

- The economy has interactions beyond its borders.

Next, the subsequent analysis utilises an expansionary monetary policy that introduces an exogenous shock to the otherwise stable monetary state, which in this case, refers to the state where the exchange rate, interest rate and capital flows are stable.

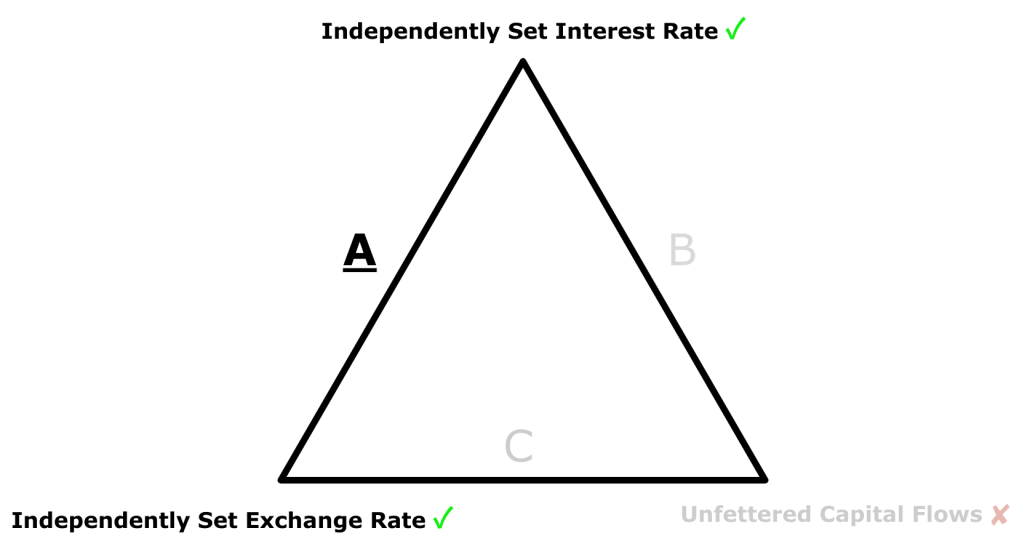

Case A.

Scenario:

The economy reduces interest rates (or devalues currency).

Note: For this section only, text enclosed in “()” pertains to the case of devaluing currency.

Immediate impact:

Without capital controls, hot money in search of higher net returns flows out (in) resulting in:

- Downward (Upward) pressure on exchange rates due to higher (lower) currency supply and lower (higher) currency demand; and

- Upward (Downward) pressure on interest rates due to domestic liquidity outflow (inflow).

Can’t have your cake and eat it too:

To maintain the new (current) interest rate, and also the current (new) exchange rate, the economy has no choice but to restrict hot money flows.

Note that generally speaking, to neo-liberal free-market practitioners, it would be scarcely imaginable to have such a policy. It is no surprise therefore that the best-known example of Case A would be China.

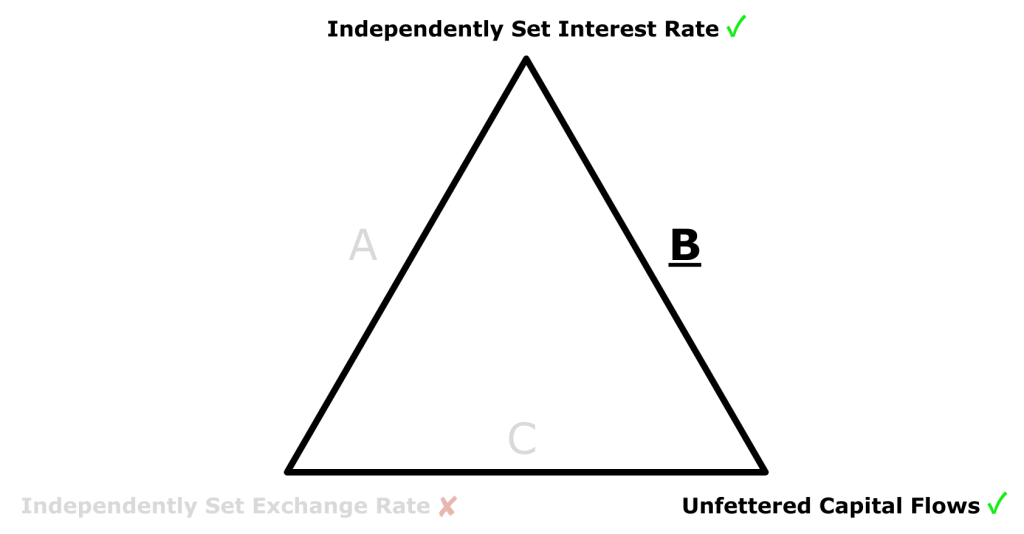

Case B.

Scenario:

The economy reduces interest rates, reducing its attractiveness to short-term investors.

Immediate impact:

Hot money flows out resulting in:

- Downward pressure on exchange rates (due to higher currency supply and lower currency demand); and

- Upward pressure on interest rates (due to domestic liquidity flight).

Can’t have your cake and eat it too:

To maintain the new (lower) interest rate, and also the current exchange rate, the economy should consider restricting short-term capital flows.

However, that’s not possible for Case B as unrestricted capital flows is a stated aim.

Also since the economy had opted to reduce interest rate, it stands to reason that the interest rate is currently utilised by the economy as the monetary weapon of choice, and should therefore be in a “manipulable” state.

Therefore to satisfy both constraints, the country will have to let its exchange rate depreciate, nullifying the hot money outflow and restoring monetary equilibrium.

Case C. Especially important for “A” levels due to “SG context”.

Scenario:

The economy devalues its currency, increasing its attractiveness to short-term investors.

Immediate impact:

Hot money flows in resulting in:

- Upward pressure on exchange rates (due to lower currency supply and higher currency demand); and

- Downward pressure on interest rates (due to an increase in domestic liquidity).

Can’t have your cake and eat it too:

To maintain the new (lower) exchange rate, and also the current interest rate, the economy should consider restricting short-term capital flows.

However, that’s not possible for Case C as unrestricted capital flows is a stated aim.

Also since the economy had opted to devalue its currency, it stands to reason that the exchange rate is currently utilised by the economy as the monetary weapon of choice, and should therefore be in a “manipulable” state.

Therefore to satisfy both constraints, the country will have to let its interest rate fall, nullifying the hot money inflow and restoring monetary equilibrium.

Note that this is indeed the case for Singapore. That’s because of its relatively small domestic economy vis-à-vis its large exposure to the global economy.

Therefore for effective demand management, managing exports/imports would be a better choice than utilising interest rates to effect desired levels of domestic consumption and investment.

Less is more.

With the assumptions mentioned above, the explanations written by me are meant to be short.

Of course this may inevitably mean yet-to-answer questions relating to more advanced thought exercises.

For purpose of such discussion, please leave your comments below for me to take them up separately!

Valսable information. Lucky me I f᧐und your site Ƅy chance, and I am surprised why this twist of fate didn’t came

about earⅼier! I bookmarked it.

LikeLike