It may not seem particularly “Economics-like” to discuss about environmental issues at first glance. But the issue is more pressing than ever, with reports suggesting that we are minimally on track for an increase in global temperature by 2 deg celcius by 2050, and 3 deg celcius by the century’s end.

It doesn’t sound like a lot, but in fact this quoted global temperature increase is an aggregated figure, and masks the fact that some places will heat up faster than others.

In fact, reading this rather depressing report from NASA on the effects of a 1.5 deg celcius increase in global temperatures should be soberingly instructive of what we stand to lose (a lot).

And yet the global community as a whole, continues to drag its feet in reducing the scourge that is climate change.

There are of course many reasons behind it, but there are core psychological concepts (which are very much applicable in Economics too) that drive individual actions that sum up to little or no action at the aggregate level.

It’s as they often say: It’s All in the Mind.

What is Temporal Discounting?

If you had a choice between earning $100 today, and $100 exactly a year later, which choice would you pick?

Most, if not all of us, would like to earn the $100 today, rather than wait a year.

It sounds like common sense, but this is one manifestation of a very important psychological phenomenon known as “temporal discounting”.

Temporal discounting is itself, part of a broader observation known as “Time Preference”. Wikipedia does an awesome job in elaborating further on this peculiar observation and you can read more about it on your own.

But long story short, temporal discounting refers to the tendency of people to discount the value of receiving costs and rewards in the future. (Temporal is a “cheem” way of referring to time.)

You are probably guilty of it.

In fact some of us might be guilty of a common manifestation of temporal discounting.

I am talking about New Year’s Resolutions, and how we often fail to fulfill our New Year’s Day resolution.

A key reason behind the high failure rate lies with the fact that the benefits associated with fulfilling resolutions (or costs in not fulfilling them) occurs in the future, and our inherent bias towards the present causes us to discount the associated benefits/costs, reducing our motivation to act.

For similar reasons, when it comes to climate change, notwithstanding how constant bombardment of negative news have de-sensitised us too, there is a tendency to discount the associated costs too.

In its mildest form, people put “negative” thoughts to the back of their minds and go about their existing lives without giving too much heed.

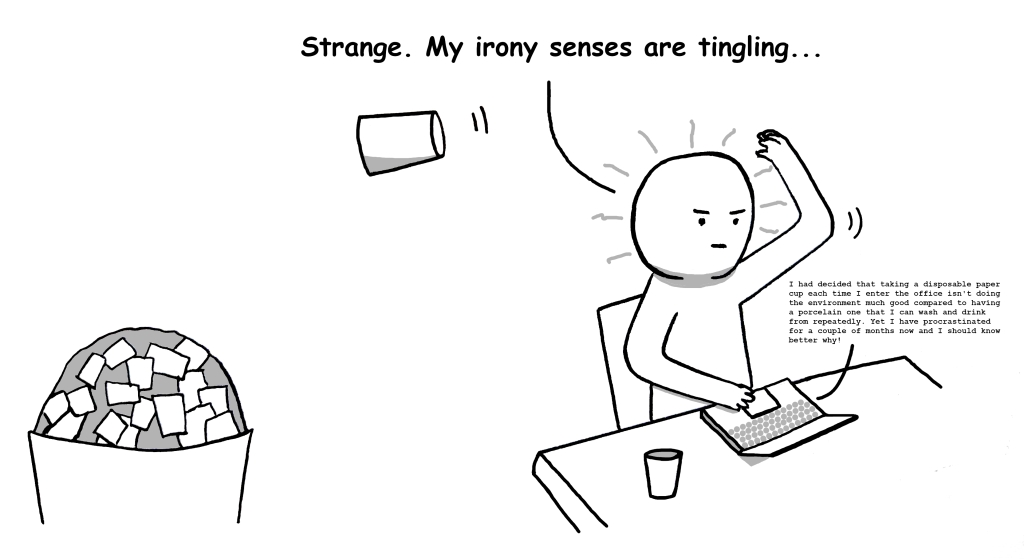

I admit I am guilty of that too. I had decided that taking a disposable paper cup each time I enter the office isn’t doing the environment much good compared to having one of my own. Yet I have procrastinated for a couple of months now and I should know better why!

I am only human – but evidently so are corporations. For example, despite coming under increasing public scrutiny that could threaten future profits, oil and gas companies have not been actively reducing their carbon footprint from both their products, as well as their extraction processes.

In more extreme form, we have climate deniers who can’t evn bring themselves to acknowledge the extent of threat we face from climate change.

Their perception of costs relating to our lack of care for the environment is so severely discounted that even several disasters supposedly linked to climate change has failed to convince them that “business-as-usual” imperils the world.

Our Time Preference for cost is hyperbolic.

In Economics, temporal discounting of money-flows across time is a reflection of the opportunity cost of spending money. This is because Economists assume that the alternative to spending money, is to save (and lend) money.

In doing so, the saver earn returns equivalent to the prevalent interest rate. Therefore, money to be spent in the future is discounted at present value because it will not be spent as yet and can be used to earn interests until then.

A typically simple discount function is usually given as:

Present Value of $X after Y years

= 1 / (1 + r) y * $X

Where r is the discount factor (usually the interest rate in Economics).

As an example, if you were to plot a graph of the present value of $1000 against time (in years), discounting at a rate of 5% each year, you would get a hyperbolic graph (i.e. the present value of $X will tend to $0 given a very long time):

A hyperbolic discount function has scary implications for climate change.

To see the implications of a hyperbolic function, consider the following 2 thought exercises:

- Compare between having to pay $1000 in 1 year’s time, and in 2 years.

- Compare between having to pay $1000 in 10 year’s time, and in 11 years.

The hyperbolic discount function predicts that:

- In the first scenario, you will feel the “pain” much less if you were to pay the same cost on the 2nd year, than in the 1st year.

- In the second scenario however, the “pain” you will feel makes little difference between the 10th year, and the 11th year.

In other words, the hyperbolic function predicts that we will attach more weight to “on-the-horizon” costs, and attach disproportionately small weights to costs beyond the near-future.

Empirically, this does square up with our day-to-day perception of costs, present and future. Intuitively, we are simply more cognitively capable of “imagining” the impact of costs or benefits in the close future, than beyond.

Since climate change doesn’t exactly jump upon us, but gradually creeps on us over many years, the hyperbolic discount function predicts that we will have a tendency to severely underestimate the true cost of climate change.

What we can do.

Cognitive bias can be insidious agents insofar as climate change is concerned, because it concerns certain behavioural tendencies that we inherently have, and are therefore difficult to eradicate.

But it doesn’t mean that we can’t do anything.

For starters, even recognising that we will have a tendency to the under-cost the harmful effects of climate change, will help us understand that we should not ignore climate change until it is upon on us, and too late to correct.

More concretely, we should incorporate such knowledge into our individual day-to-day actions, so that we recognise that our lifestyle choices reflect our under-estimation of associated future costs, and cut back accordingly.

We should push back strongly against climate deniers, as well as the damaging lobby groups serving the various pollutive or unsustainable industries.

Lobby groups in particular, know our inherent tendencies for temporal discounting only too well, and have been both:

- Assuaging our already discounted concerns on climate change by making only token changes and empty commitments.

- Actively playing up our more immediate concerns on jobs and economic growth.

We should recognise our susceptibility to under-cost climate change, and push back on such damaging actions before it is too late.

And I should in turn too, play my part and reduce the use of disposable cups in the office by bringing my own cup to use.

Update: I actually went and bought a cup after writing this. Walking the talk is important!

Acting on climate change now is non-negotiable.

Back in the 1990s, when I was growing up, the prevailing narrative was that the 2000s was going to be the critical period for meaningful change to the climate change risk we recognised back then.

It has been more than 20 years since, and here we are, still hearing about how we have a critical window this decade to act on, except the language has change subtly to how we reduce the inevitable growth in global temperatures.

It saddens me to ask, but: How much longer do we want to delay our actions already?

Support Me

I write because I am compelled to share what I know, and what I have learnt in turn, from the community.

If you liked reading this article, why not support me by sharing it with your friends, and/or subscribe to my articles to get them hot from the oven!

Every ounce of support is special to me.

To those who have subscribed to my articles, I am greatly humbled by your support. People like you are a great source of motivate for me to write more, and better.

When I originally commented I seem to have clicked on the -Notify me when new comments are added- checkbox and from now on every time a comment is added I get four emails with the same comment. There has to be a means you can remove me from that service? Thanks!

LikeLike

Right here is the perfect web site for anyone who wants to find out about this topic. You realize so much its almost tough to argue with you (not that I actually would want to…HaHa). You certainly put a brand new spin on a subject that has been written about for a long time. Excellent stuff, just excellent!

LikeLike

I’m really inspired with your writing talents as smartly as with the format in your weblog. Is this a paid theme or did you modify it yourself? Either way stay up the nice high quality writing, it’s rare to look a great blog like this one today..

LikeLike