A common question from students pertains to whether FDI (Foreign Direct Investments) to a country is counted as part of “I” in the calculation of the National Income (C+I+G+X-M).

The quick answer to above question is: Yes, FDI indeed counts towards “I” for the given time period.

To understand why, we need to look at the following concepts.

What is FDI?

FDI is defined as:

The good news is that students are not expected to reproduce detailed definitions of FDI in the exams.

Students must however know that a key concept of FDI is that the FDI flowing into the host country will be used ultimately for Gross Fixed Capital Formation.

What is Gross Fixed Capital Formation?

Gross Fixed Capital Formation (GFCF) refers to the net increase in physical assets (investment minus disposals) within the measurement period.

Examples of GFCF includes buying equipments for manufacturing or transportation.

Interestingly, land purchases are not usually considered as GFCF. The rationale behind this is that the land was not “created” and had merely “changed hands”. By similar token, land reclamations on the other hand, are considered to be GFCF because land (a tangible asset) had been created.

In the context of National Income Accounting, GFCF’s other form is “I” in “C+I+G+(X-M)”.

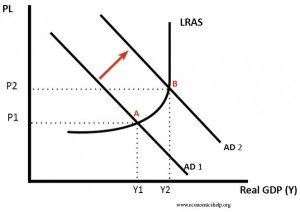

So as you can see, the direct effect that FDI has on the host country, is Economic Growth, which occurs as the Aggregate Demand increases, due to an increase in “I”.

Because FDI involves capital flows across countries, there will inevitably be effects on the Balance of Payments (BOP) as well. The country that is investing will have its BOP worsened, with the opposite effect happening to the receiving country, in the short-term.

Is FDI always good for the host country?

The answer as always, depends on various factors.

It is generally true that FDI has an immediate positive impact to the macroeconomic indicators:

- Economic Growth is stimulated as FDI increases the GFCF, which increases AD.

- Unemployment is reduced because FDI leads to more job opportunities in the host country.

- BOP is improved as there is an increase in capital flow into the host country.

A good testament to the efficacy of an FDI-led growth (i.e. encouraging FDI into the country to power the economy) would be Singapore.

Last year, FDI worth US$70B flowed into Singapore, putting it in 5th spot for the top FDI destination, continuing a trend that we have been pursuing for half a century.

In terms of the World Economy, it is possible for everybody internationally to be better off, based on the Theory of Comparative Advantage.

A key implicit assumption in the application of Comparative Advantage to frame the advantages of FDI is that FDI flows into the host country because it possesses comparative advantage in various industries.

For example, textile manufacturers have invested significant amounts of capital in Bangladesh to take advantage of competitive labour rates to reduce their costs of production for clothes. In 2014 alone, textile-related FDI amounted to more than US$400M.

Based on that logic, it is possible for global output of goods and services to increase due to specialisation, which would in theory, raise the Standard of Living of all involved parties.

FDI can have ill-effects on the host country.

The Theory of Comparative Advantage is a fairly benign and logical explanation for FDI flows in general. Obviously there is more than one explanation to explain foreign investments to the host country.

FDI as a “let’s be friends tool”

FDI is an excellent diplomacy tool, and it has been seen on multiple occasions, most recently with China investing in various ASEAN countries, most notably in Cambodia and Laos.

As this report notes, the key driving force behind China’s strong FDI push into Cambodia is largely driven by political considerations, and not necessarily economic ones.

In such a case, it is hard to say conclusively that FDI is bad for the host country (it certainly did good for Cambodia whose economy could certainly use such help). What is certain however is, in many cases, such economies become dependent on the politically-driven FDI.

Obviously, such an FDI strategy hardly builds resilience into the economy. The reasonable assumption here is that Economic Growth due to economic competitiveness is a more sustainable growth strategy in the long term.

Aside from politically-driven FDI being an inherently bad strategy for the economy, there are strong incentives by the government to go out of their way to prevent long-term solutions aimed at improving sub-optimal political situations.

This is because the removal of such issues would also remove the foreign intervention considerations that led to the FDI inflow in the first place. This could explain why Cambodia has been uncooperative towards ASEAN which is an aim of the Chinese FDI.

Needless to say, being rude to your neighbours is an arguably bad long-term strategy, especially if you are going to have to rely on your “big buddy” who lives another street away.

Aside from the bad side of poltically-motivated FDI, FDI may also be motivated by the desire to circumvent well-meaning regulations.

Perhaps ironically, the Theory of Comparative Advantage can actually explain such a sinister motive – many MNCs often re-locate their “dirty” side of their business to third-world countries because they have a comparative advantage in lack of regulations, which allow MNCs to pursue their strategy of improving cost competitiveness as regulations usually leads to added costs.

Obviously this has negative long-term effects on the host country. Classic manifestations to this includes labour exploitation and environmental degradation, amongst other negative externalities in production.

One particularly bad case was the Bhopal Union Carbide disaster, which occured when highly toxic gas was accidentally leaked, causing the deaths of many thousands, and affecting at least half a million people.

Even when FDI is pursued as a strategy on strong economic grounds, there have been arguments that a long-term FDI-led strategy is not the best one.

In addition to exposing the host country to risks to the world’s economy (which in Singapore’s case is inevtiable given our very small domestic consumption), FDI often crowds out domestic industries, which hinders the host country from building up its own capabilities.

This article provides excellent arguments that FDI-led strategies should not be pursued as a sole strategy indefinitely, using Singapore (ouch) as the key point.

In Conclusion

FDI, as understood in our definitions laid out earlier, is in general a positive force at least in the short-term. However for various reasons, FDI can give problems to its host country in the long-run, the ultimate effect being dependent on the motivations and utilisation of the FDI.

I hope that you have enjoyed reading this article of mine. I am giving my time to sharing my knowledge and every bit of support means a lot to me! Do drop me a comment or share this article on social media with your friends.

For more information about my services as a JC Economics tutor, do visit my website here.