I had previously written a piece about the need to understand and differentiate the concepts of excludability and rivalry well.

Of particular note was the fact that excludability, rather than rivalry, was the key determinant behind the free market price of zero for public goods.

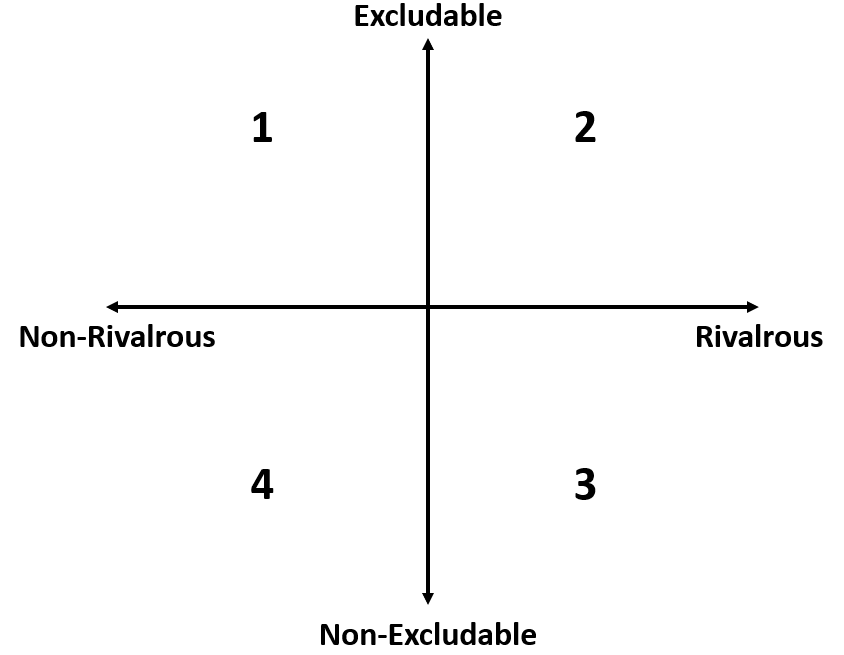

Anybody who has some grasp of the concept of combination, would have realised also that having 2 distinct properties raises the possibility of having 4 different categories of goods to look at.

A quick recap on Excludability and Rivalry

As most of us know:

- An Excludable Good is one which can be excluded from non-paying customers;

- A Rivalrous Good is one where its consumption by one consumer does not reduce the ability of another consumer to consume it.

More in-depth explanation can be found in my previous post.

Combinations of Excludability and Rivalry

Earlier Neo-classical Economics’ framework had focused a lot on private consumption of goods and services and the ensuing market behaviour.

And then in the middle of the 20th century, a really smart chap named Paul Samuelson developed a theoretical framework for public goods.

It didn’t take long before others figured there was a small problem – in many cases, goods didn’t fit cleanly into the private-public good dichotomy.

These came to be known as impure public goods – goods that were either:

- Excludable, but non-rivalrous or;

- Non-excludable, but rivalrous.

One easy way to visualise possible combinations of both properties, is to make use of a quadrant diagram:

Each possible combination of excludability and rivalry occupies a quadrant:

- Excludable, non-rivalrous

- Excludable, rivalrous

- Non-excludable, rivalrous

- Non-excludable, non-rivalrous

Quadrant 2 and 4 should be instantly recognisable to students – they represent private goods and public goods respectively.

Quadrant 1 and 3 are seldom taught in “A” levels – if at all, so these goods, a.k.a impure public goods, will be of main interest in this article.

Club Goods

Quadrant 1 has the characteristics of excludability, but non-rivalry.

Such goods are known as club goods, because non-paying consumers can be excluded from consuming them. But once the good is paid for, the consumption is non-rivalrous, at least up till the point of congestion.

Examples of club goods include toll roads, private parks, subscription TV/music channels, concerts.

Since the club good is non-rivalrous, the marginal cost of producing the next unit of club good is essentially zero.

Therefore in charging a price for a good that costs zero to produce for each next unit, the suppliers essentially introduce artificial scarcity to society.

Club goods are therefore allocatively inefficient because charging for the good reduces consumption, and therefore societal welfare, when more could have been consumed at no additional cost to society.

Some experts argue however that the loss in efficiency is more than outweighed by the free market provision of the club good because:

- Without the ability to exclude, the club good is essentially a public good and will not be produced by the free market.

- Free market producers tend to produce goods more in accordance to the wants and needs of consumers (i.e. more dynamically efficient).

In short, money makes the world go round, and the club good exemplifies it.

In that respect, club goods are of particular interest because if non-excludability can be incorporated into the public good, then the free market can be tapped on for the production of the good, freeing up government resources and also introducing more dynamism to the market.

Consider online general search engines such as Google search – it is a public good for most of us, and yet it is produced by private companies.

The archetype example, Google, has been able to provide such a wonderful product as a public good to us, because it earns revenue instead, from related products such as Ads and Business Suite.

The freemium model, where basic products and services are provided as public goods, but more advanced features require payment, combines elements of both public goods and club goods, follows a similar concept.

This payment model has been utilised heavily in the tech software industry, and has been cited often as instrumental in improving many of our lives at reasonable cost.

Common-Pool Resources

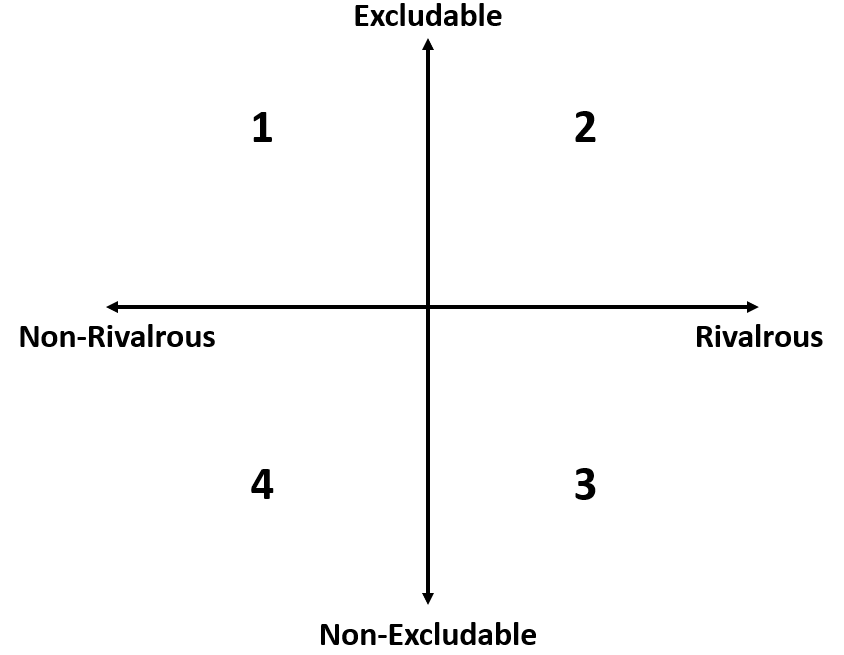

We revisit the quadrant diagram again:

Quadrant 3 has the characteristics of non-excludability, but rivalry.

Such goods are known as common-pool resources.

In such cases, non-paying consumers cannot be excluded from consuming them, but the consumption of the goods reduces the quantity available to others.

Examples of common-pool resources include sea-fishes, forests, rivers.

You may have noticed that the examples cited for common-pool resources are associated with natural resources.

This is no coincidence – because such resources are often associated with lack of property rights, which causes non-excludability.

Throw in the fact that these resources often require time to regenerate, and we get a case of rivalry too (i.e. the resource gets utilised faster than it can regenerate, resulting in depletion).

Common-pool resources are frequently over-exploited, which can be explained by the Prisoner’s Dilemma I had discussed in my previous article.

To see this, let’s say there is a fishing ground, and 2 competing fishermen, A and B, whose objective is to catch as many fishes as possible to sell.

The fishing ground requires time to regenerate, and for fishing to be sustainable, the total fishing weight must not exceed 10kg per day. Since there are 2 fishermen, assuming equal catch per session, each fisherman must not fish beyond 5kg per day.

Assuming that each fisherman can fish up to a maximum of 15kg per day based on their present equipments, the possible outcomes are:

- If A and B each fish 5kg each day, both will be able to fish for a long time, and lead less-than-rich lives.

- If A betrays B by fishing 15kg, but B remains fishing at 5kg each day, A will get rich while the fishing stock lasts, while B finds it increasingly hard to maintain his catch.

- If A and B both fish 15kg each day, both of them will get rich for a short while, and then have to pack up and find another livelihood as the fishing stock collapses.

If you were in A’s shoes, you would always choose to over-fish, because:

- If B had kept to 5kg, A can get richer by over-fishing.

- If B over-fishes, A should also over-fish because the fish stocks would collapse later anyway and you would not want to experience “FOMO”.

What then results, is a dramatic-sounding “Tragedy of the Commons“, where individual users, acting independently according to their own self-interest, behave contrary to the common good of all users by depleting or spoiling the shared resource through their collective action.

The Tragedy of the Commons is a major reason behind the environmental issues we have today.

When I grew up before the turn of the millennium, textbooks and documentaries have been warning us about the critical years ahead, during which our tendency to over-exploit resources must be corrected.

Today, the same environmental call-to-arms still goes on, and yet we seem further than ever from the solution – which gives an idea of how difficult it is to solve the issues of common-pool resources .

There are potential solutions to the common-pool resources problem.

Extending property rights to common-pool resources is one way. But ownership can often be contentious amongst the various parties, and some resources such as fishes, do not stay in a particular zone, making it difficult to assert ownership rights.

Laws and regulations often result in cat-mouse games between the enforcers and the regulatory targets, resulting either in lax enforcement or ever-increasing complexities in the regulations.

Perhaps the more sustainable approach would be to alter cultural norms such that those who abuse common-pool resources get marginalised, and those who make effort to protect them receive social rewards.

Unfortunately this approach requires time, time that we may not have, as norms can be difficult to change, as evidenced by the trend of countries even back-pedaling on environmental commitments in recent years.

Lend your support!

I hope that you have enjoyed reading this article of mine. I am giving my time to sharing my knowledge and every bit of support means a lot to me! Do drop me a comment or share this article on social media with your friends.

To find out more about my services as a JC Economics tutor, visit my website here.

I just turned 68 this year and I really admire your writing!

LikeLike

If more people that write articles involved themselves with writing great content like you, more readers would be interested in their writings. I have learned too many things from your article.

LikeLike

Enjoyed reading through this, very good stuff, regards . “A man may learn wisdom even from a foe.” by Aristophanes.

LikeLike

Thanks for sharing, this is a fantastic article post.

LikeLike