Here’s a fun fact – the monetary policy implemented by the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) as we know it today, turned 40 this year.

Much of the principles behind how MAS operates Singapore’s exchange rate are covered in the “A” level exams for Economics, and are more than sufficient in understanding the broad picture in Singapore’s macroeconomic management.

But, having taught the final lessons for this year’s “A” level candidates, I had more free time on my hands, and got down to the more technical aspects of the exchange rate policy. Students would be relieved to know that these aren’t examinable for the “A” levels.

Ordinarily, this wouldn’t have been a direct trigger for writing an article. However, a particular line in the texts piqued my curiosity:

“Domestic interest rates have typically been below US interest rates and reflect market expectations of a trend appreciation of the Singapore dollar over time.”

This was potentially something new to me since I hadn’t thought about it in such light. So naturally, I delved deeper into the publicly available scriptures by MAS, and duly found this:

“In addition, the relationship between the interest rate and exchange rate in Singapore is generally well-characterised by the uncovered interest parity relationship”

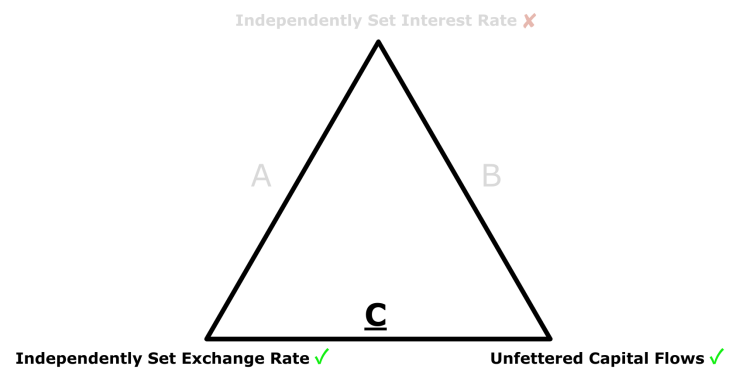

The Impossible Trinity.

To fully appreciate these observations on Singapore’s exchange rate policy, we turn first to a concept that is not taught in full details, but which relevant parts are implicitly expected to be familiar to students.

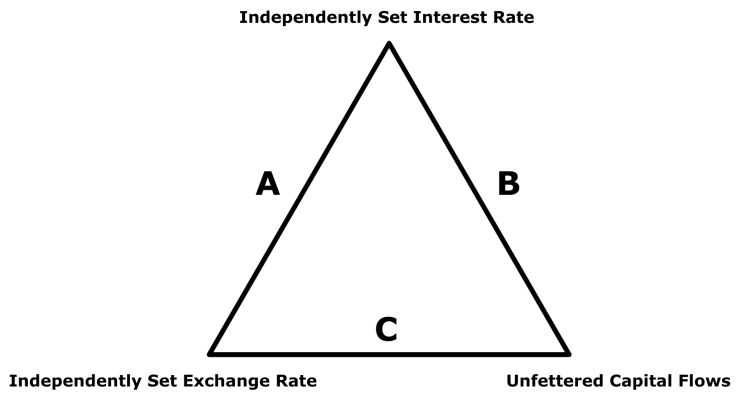

For the uninitiated, The Impossible Trinity (a.k.a the Policy Trilemma) asserts that policy-makers may only choose to achieve 2 outcomes out of the possible set of 3:

- Independently set interest rate;

- Independently set exchange rate; and

- Unfettered capital movements in/out of the country.

A more detailed explanation to the underpinnings of the Impossible Trinity can be found in my previous article here.

If each side to a triangle is used to describe a particular combination of 2 outcomes as above, then the case of Singapore and her current monetary policy stance is best described with case “C” as below:

In making a conscious decision to pursue case “C” for reasons that should be familiar to students, and which are well-elaborated by MAS, Singapore has effectively given up control over its interest rate and left it to the whims of global influences.

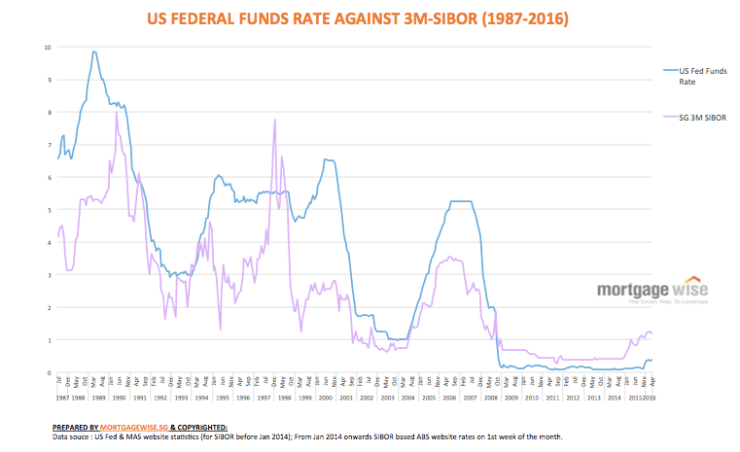

As noted in my previous article, the SIBOR (Singapore Interbank Offered Rates), which is the reference interest rate for Singapore, closely tracks the prevailing US Fed Funds interest rate.

Interestingly, it had escaped my attention that in addition to the clear correlation between the SIBOR, it can be observed that at least prior to the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, the SIBOR has been persistently tracking below the US Fed Funds interest rate.

Cross-border arbitrage.

With unfettered capital flows, cross-border borrowing and lending becomes a reality, and this gives rise to increased opportunities for arbitraging.

Arbitraging refers to the simultaneous purchase and sale of assets across markets for purpose of making profits from differing prices. Here, arbitraging can take place by borrowing at a low interest rate, and lending the borrowed sum at a higher interest rate in another market, which will more than offset the repayment of the borrowed sum.

To see how this works, we can set up a hypothetical situation between Singapore and Malaysia:

- Prevailing interest rate in Singapore: 0.44% per annum;

- Prevailing interest rate in Malaysia: 1.75% per annum;

- 1 SGD currently buys 3 RM; and

- The exchange rate is expected to remain stable.

As you will see later, the final point is of particular interest to us.

Our hypothetical arbitrager in Singapore smells a profit opportunity, and borrows S$1,000 in Singapore, to lend in the Malaysian market for 3,000 RM.

In a year’s time, our arbitrager pockets 3,225 RM, which he then converts back to SGD as S$1,075.

He then fulfills his borrowing liability of $1,004, leaving him with a profit of $71. The motivation for arbitraging here should be plain to see.

It should be mentioned that this example is an extremely simplified representation of real-world cases. In particular, we have implicitly assumed that cross-border transactions are frictionless, and assets are made and valued similarly across markets. Needless to say, neither assumptions hold true in most cases, and contribute immensely to complex arbitraging scenarios instead.

The exchange rate appreciates instead.

Assuming these implicit assumptions hold though. our example can become less straightforward still, when we remove the constraint of stable exchange rates, and inject an expectation of appreciating SGD instead:

- Prevailing interest rate in Singapore: 0.44% per annum;

- Prevailing interest rate in Malaysia: 1.75% per annum;

- 1 SGD currently buys 3 RM; and

- The exchange rate is expected to be 1 SGD : 3.5 RM in a year’s time.

Similar then to the earlier example, our arbitrager pockets 3,225 RM in a year’s time. Unfortunately for him, the SGD has appreciated and the money he earned translates to only S$921, which yields him a loss of $83 instead (after paying back S$1,004)!

In fact, assuming certainty in the projected exchange rate as above, it can be shown using a similar hypothetical situation that an arbitrager from Malaysia would have profited instead:

- Our Malaysian arbitrager borrows 1,000 RM;

- He lends that sum in Singapore as S$333 (old exchange rate);

- In a year, he pockets S$335, which translates to 1,172 RM (new exchange rate);

- He returns 1,075 RM, and keeps 97 RM as profit.

Interest Rate Parity.

Clearly, there are 2 key variables that in theory, affect our arbitrager’s decisions: The respective countries’ interest rates, and the expected future exchange rate.

In practice, unless the respective debts have differing maturity periods (the point at which the debt must be returned), the respective interest rates are usually agreed upon by forward contracts to reduce risks.

This leaves expectations to the exchange rate as the key determinant.

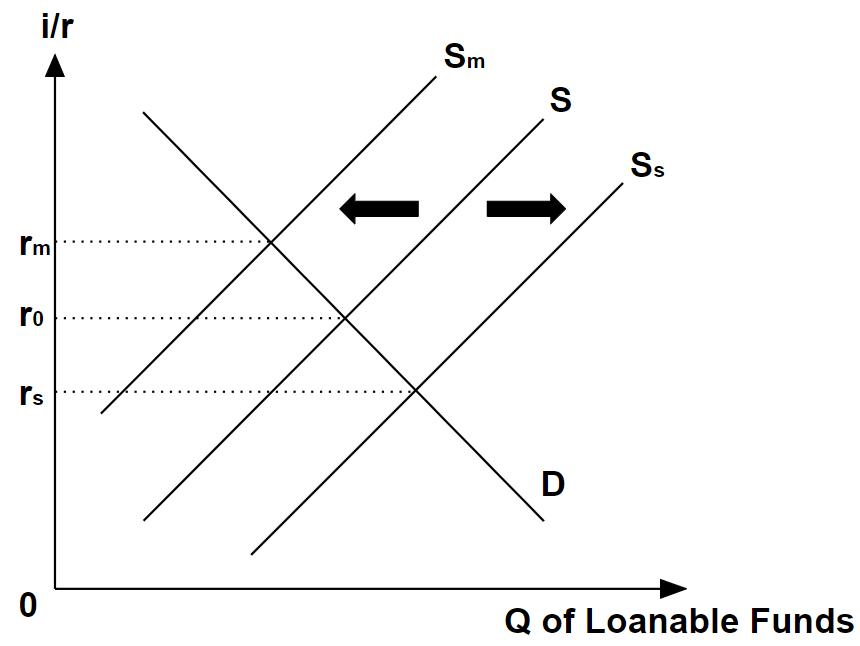

To complete our story then, if we assume that every investor in both countries share similarly rational thoughts and information at their disposal, then their collective decision (that Singapore is a more attractive destination for loans, and Malaysia for borrowing) would cause a simultaneous rise in supply of loanable funds to Singapore, and a fall to Malaysia’s.

The movements to the respective countries’ supply of loanable funds ultimately leads to upward pressure on Malaysia’s interest rate, and a downward pressure on Singapore’s interest rate. This is indeed borne out, at least in Singapore’s case, which as MAS notes, generally exhibits lower-than-global-norm interest rates under usual circumstances.

Interestingly, the downward pressure on Singapore’s interest rate serves to negate the source of arbitraging opportunities brought on by future appreciation of SGD, by reducing the rate of returns on loans.

It can be shown that, similar to other market equilibrium tendencies such as the Marginalist Principle, these opposing forces ultimately result in market-clearing interest rates, given the independently-set exchange rate in Singapore.

In effect, these describe the Uncovered Interest Rate Parity – where either interest rate and exchange rate adjust in the presence of unfettered cross-border capital flows, depending on monetary policy stance dictated by the Impossible Trinity (cases “B” or “C” below).

This is in fact a similar theme to the Purchasing Power Parity, where prices of the same good in different countries, should have the same financial impact to anybody globally, taking their respective costs of living into account.

Uncovered vs Covered.

The scenario explained in detail above, described an Uncovered Interest Rate Parity situation – so named because the future exchange rate that underpinned the determination of the present interest rate, is not literally covered by any contract, and are exposed to risks of the expectations not being borne out.

I had mentioned earlier that interest rates aren’t usually the key driving forces behind the Interest Rate Parity because the terms of debts tend to be agreed upon inclusive of prevailing interest rates.

It follows, rather logically, that there is nothing also that prevents the transacting parties from agreeing upon a binding exchange rate to be applied when the debt monies are converted to the appropriate currencies.

This is especially true when we consider that transacting parties tend to be risk-averse. Such case where the key deciding factor depends instead on exchange rates as laid out in forward contracts, is described as Covered Interest Rate Parity.

At least for today’s discussion, the distinction between both concepts are immaterial and you can read more about it here.

And that’s a wrap! If you would like to leave comments or questions, feel free to do so here below.

Es ist eigentlich eine schöne und nützliche Info. Ich bin froh, dass Sie diese nützliche Information mit uns geteilt haben. Bitte halten Sie uns so informiert. Danke für das Teilen.

LikeLike

I think other web-site proprietors should take this website as an model, very clean and great user genial style and design, as well as the content. You’re an expert in this topic!

LikeLike