As a student taking Economics at “A” Level nearly 20 years ago, the Circular Flow of Income was probably mentioned no more than 10 times during lessons and the subsequent prep for exams.

Fast forward to today, having taught Economics as a tutor for the last 13 years, few of my “A Level” and “IB” students could competently apply the Circular Flow of Income in the exams. Some things don’t change it would seem.

The exam syllabi for both “A Level” and “IB” offered at the various difficulty levels (H1/H2 for the former, and SL/HL for the latter) are clear that the Circular Flow of Income is a key concept that students are expected to master for Macroeconomics.

Yet this gap in knowledge is exceedingly common due to a few reasons:

- The concept is simple and is taught as a foundation to Macroeconomics;

- Schools teach quickly to cover the mountain of materials, frequently glossing over “easier” concepts such as this;

- Other Macroeconomic concepts, particularly the AD-AS models, readily explain the same stuffs, and contain more details; and so

- The Circular Flow of Income is rarely tested, at least explicitly, in the exams.

The last point, in particular, is probably the main motivation for students in what might be described frequently as “purposeful ignorance”.

The not-so-great news is that the Circular Flow of Income has appeared in the exams – and I back my claim up with this thread from Reddit.

Increasingly too, schools have also explicitly required the use of this concept in analysing specific scenarios, preventing the use of more traditional approaches used by students such as the afore-mentioned AD-AS models:

Given that the concept is not actually difficult, and can be easily committed to working memory with a few key understandings, students are unnecessarily risking the possibility of being unable to answer exams in questions.

So in addition to my notes (which are free-of-charge), here are some simple key facts about the Circular Flow of Income that students must know to fully understand how it is applied in the exams.

This post assumes that you have a basic grasp already of the Circular Flow of Income, and its components. If you don’t already, you can refer to my notes, refer to your textbook, or even do a Google search for great explanations like this one.

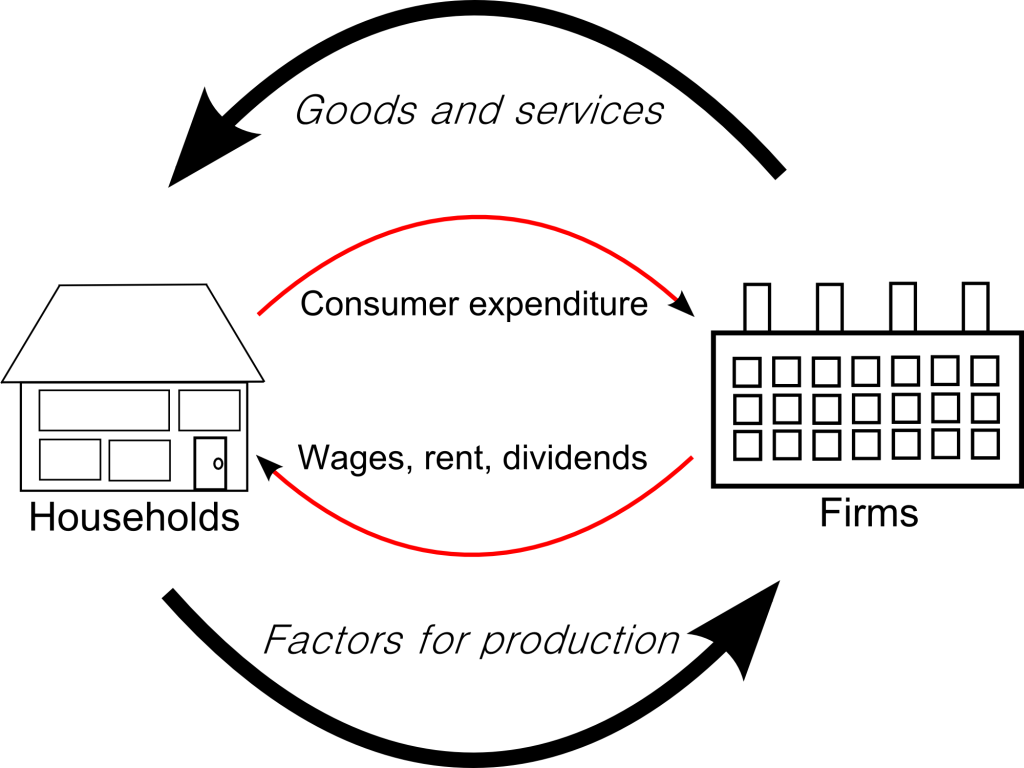

1. We are more interested in the monetary flows.

For the exams, that is.

What I am talking about, is how textbooks frequently illustrate the Circular Flow of Income depicting how households and firms interact by way of goods, services flow in addition to income and revenue:

Ostensibly, this is to present a more “complete” picture of the nature of transactions between firms and households. To most students, more lines and labels are hardly desirable.

The good news is that the Circular Flow of Income can be illustrated in the exams with only the flows associated with money (i.e. the red arrows in the above diagram only).

With less things to depict in the exam, the easier the exam prep gets.

2. The Steady State assumption.

Because the Circular Flow of Income, like Rome, isn’t drawn to represent the state of the Economy for a day, the income flows are expected to be continuous in a properly-functioning economy.

Logic dictates that the Circular Flow of Income must have a tendency to self-correct from external perturbations. Otherwise, the system will be unstable and fail to sustain itself over time.

Extending that logic further, there must exist a steady-state that the Circular Flow of Income would always try to return to.

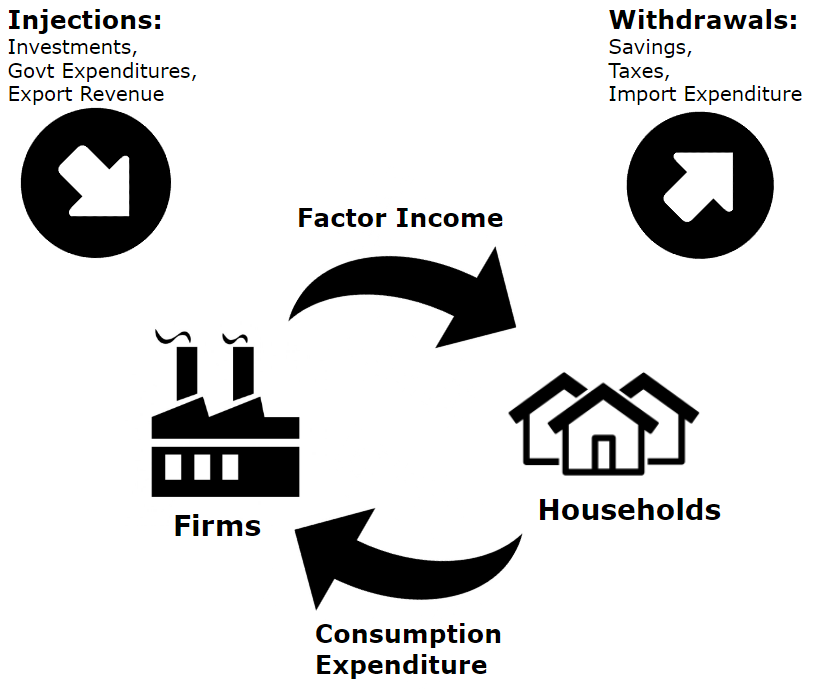

Consider that the Circular Flow of Income has, broadly speaking, 4 key money flows within (between households and firms), and interacting with external systems (a.k.a the Injections and Withdrawals):

In a system that holds a finite quantity of money within, a steady state cannot be achieved if there is persistent difference in size between the money flows in the respective internal or external flows.

For example: If Factor Income exceeds Consumption Expenditure, the firms will eventually run out of money to continue generating the Factor Income flow, disrupting the Circular Flow of Income.

The vice versa argument holds as well (i.e. Consumption Expenditure exceeds Factor Income).

A similar argument can be made also, for the case of Withdrawals exceeding Injections.

However, as I have written before, the case where Injections exceed Withdrawals proves tricky for several reasons:

- Countries may print money; and

- Current account imbalances can persist with continued offsets from corresponding capital account movements.

Economists generally recognise that global imbalances under long-run scenarios tend towards self-correction, although the debate is still proving extremely contentious.

In the end, to keep matters simple for “A Level” and “IB” Economics students, we rather simplistically assume that in the long-run, net Injections will similarly be eliminated through the Circular Flow of Income’s self-correcting mechanisms.

The key point is that the starting point for any analysis in the exams pertaining to the Circular Flow of Income, must always be such that:

- Injections = Withdrawals

- Factor Income = Consumption Expenditure

In particular, the same steady-state assumption is what allows for GDP to be calculated by either the Income, Expenditure or Production approach, since:

- Total Factor Income =

- Total Consumption Expenditures =

- Total Value of all Goods and Services Produced.

3. Analysing economic shocks using the Circular Flow of Income

Because the Circular Flow of Income can be used to derive the GDP level of the country, it can be used to understand the impact of economic shocks to the economy’s GDP.

There are many permutations to how economic shocks alter the Circular Flow of Income, but typically the following steps are followed:

3.1. Determining whether the shock is one-time or structural.

One-time shocks are fed directly to households or firms, which then alters the Consumption Expenditure and Factor Income accordingly, without initially altering the Injections and Withdrawals.

For example, a one-off government stimulus to households will, in sequence:

- Increase the Consumption Expenditure;

- Increase the Factor Income;

- Increase both the Injections (investment) and Withdrawals (saving, tax, import).

Structural shocks on the other hand, tend to alter both the internal and external flows simultaneously.

For example, an appreciation of exchange rate will cause (not necessarily in sequence):

- Factor Income to decrease due to firms cutting back production;

- Consumption Expenditure to decrease due to reduced factor demand and households’ higher propensity to import;

- Imports to increase, but savings and taxes to fall due to lower households’ income.

3.2. Working towards the steady-state.

Regardless of the shock, the final outcome must always be such that the steady-state is returned, by means of counteracting changes in both internal and external money flows.

The self-correcting outcomes can be generalised as:

| If the shock originates at: | Then: | |

|---|---|---|

| #1 | An Internal Flow, | The Injections and Withdrawals will adjust. |

| #2 | The Injections, | The Withdrawals and Internal Flows will adjust. |

| #3 | The Withdrawals, | Other Withdrawal components will adjust, as will the Internal Flows (which triggers Flow #1) |

Needless to say, this might not be the clearest of explanations, so feel free to chat with me if you have a burning question and would like an immediate response. Otherwise, leave your comments below.

Sample Analysis.

We can try an example, from one of the past year’s exam questions (SAJC’s H2 Prelims paper in 2022), to have a sense of the self-correcting mechanism:

Fiscal policies should enable green and durable economic growth. As part of the Green Plan 2030, Singapore has introduced a carbon tax and is setting aside $60 million to further support technological adoption in the agri-food sector.

Using the circular flow of income, explain the effects on national income when a country implements expansionary fiscal policy. [10]

Jumping straight into the effects proper (please don’t do this in the exam!):

- Government expenditure will increase directly;

- The firms have additional funds to produce (hire) more and increase factor income, and increase investment (injection);

- Households increase consumption expenditure with higher income, but also save more, get taxed more and import more (withdrawals will increase).

- The net result will be higher GDP (due to increased and equal internal flows), and higher and equal levels of injections and withdrawals.

Concluding remarks.

The simple-looking Circular Flow of Income can be difficult to grasp if the above underpinnings are not well-understood. Fortunately as we can see, the logic behind it is not exactly rocket science.

And as always: Practice makes perfect!