I have been writing on various Economics theories and associated applications in recent articles, with the approach of the “A” level exam. Today however, I thought I would like to take a step back, and address a very fundamental aspect of the Free Market system.

By convention, we understand the Free Market to be an idealised resource allocation system where the prices for goods and services are determined by the open market and consumers, and are free from any intervention by a government, price-setting monopoly, or other authority.

However, today I will show you that contrary to the above statement, the Free Markets is neither natural, nor self-sustaining in the absence of various supporting institutional frameworks.

Although the contents of today’s article will obviously not be tested during exams, knowing the premises of the Free Market phenomenon is key to understanding the underlying mechanisms behind Economics as taught in JC, as they are nearly all based on the Free Market system.

The Free Market is not the only resource allocation system.

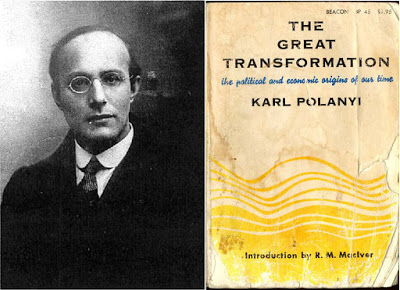

You might find it hard to believe that a human society can exist without some hint of Free Market in everyday exchanges of goods and services. But in 1944, a famous Economics historian and sociologist, Karl Polayni, wrote a well-known book: The Great Transformation.

Polayni wasn’t content with how contemporary explanations of Market Economics came to see the market system as the default framework for humans to allocate their resources.

A key implication of this bias was that it narrowed our perception of alternatives to the Free Market, particularly when it came to understanding and tackling issues related to Market Failures. Polayni asserted that the Free Market wasn’t “natural” at all. In fact, what we know to be the Market Economy was preceded by at least 3 forms of resource allocation system.

System 1: Redistribution

This happens when trade and production is focused to a central entity such as a tribal leader or feudal lord and then redistributed to members of their society.

System 2: Householding

An economy where production is centered on individual households. Family units produce food, textile goods, and tools for their own use and consumption.

System 3: Reciprocity

A system where the exchange of goods is based on reciprocal exchanges between social entities.

Do these resource allocation systems sound familiar to you? If they do, it is because they still exist in varying extents. Consider a typical day for most of us:

- You begin the day by harvesting your self-grown greens from your small garden and cooking them for your family members. (Householding)

- You then receive a letter from the Government containing your GST rebate voucher. (Redistribution)

- Finally, you sit down to wrap a gift for the upcoming Christmas event at your school. (Reciprocity)

The Market Economy needs a Market Society.

Polayni’s point was that the resource allocation configuration found in a society isn’t borne out of some simplistic “natural outcome”. The adoption of such a system is deeply intertwined with other factors such as the environment and cultural norms.

He argued that for the Market Economy to be adopted, the society would also needs to be a Market Society. A Market Society is one where market forces dominate the exchange of goods and services. Or in his own words: “Instead of economy being embedded in social relations, social relations are embedded in the economic system.”

Thus for the Market Economy to happen, there must first be changes in society to switch from the prior dominant systems of Reciprocity, Redistribution and Householding. Without going too much into historical detail, let’s think about this a little more.

The Free Market requires strong institutional support to work.

Imagine living in a society where there are no laws to safeguard property rights. A society where finders, keepers is the norm and confiscation of your possessions is even sanctioned. Do you think it would be possible to sell any goods and service the way we know it today in that environment?

Your goods will be stolen if you try to sell them and you wouldn’t produce any more than you can consume immediately because of security concerns.

You could hire security guards or arm yourself to the teeth to make sure your commercial activities could carry through. But it would be cost prohibitive and passing some costs to your customers could lose you business. Wait – can you even trust your guards?

The point I am trying to bring across is that the Free Market cannot really be “free” without strong and clear institutional support, in addition to cultural ones.

A key implication is that the “Free Market” carries implicit costs to society as a result, and requires a set of pre-requisites for it to work well. The Free Market requires:

- Legal regulations to clarify and support property rights.

- Enforcement of Law and order.

- A monetary system

Many students often write pro-market points in their essays, without realising that it isn’t as simple as letting the Free Market happen by “magic”.

The need for strong institutional supports also means that in some cases such as “failed states”, the Free Market simply won’t work efficiently (if at all) as the civil institutions are weak. In extreme cases such as in Afghanistan, “well-meaning” donors advocating the use of the Free Market for food supplies led instead to starvation.

Is the Invisible Hand benevolent?

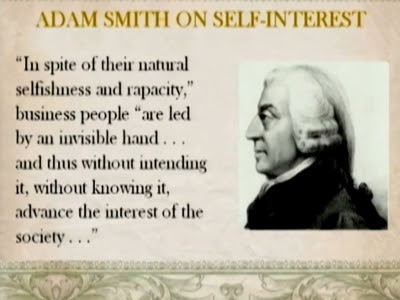

Perhaps one reason why many students often place excessive faith in the Free Market has to do with the common use of Adam Smith’s famous phrase “The Invisible Hand”.

The “Invisible Hand” referred to the decentralised nature of Market Economies in efficiently allocating resources within the society through each individual’s transactional purposes. Because many of us do not dwell on this statement longer, we implicitly accept the “Invisible Hand” to be a natural behaviour in human beings, and therefore the Free Market must be the default state of the economy.

Ironically, there is still a huge debate about what Smith meant exactly, with many believing that Smith didn’t actually advocate for a Free Market to be utilised for every situation, much less in the strongest terms. The Free Market is not a panacea for every resource allocation issue.

While I had set out to question the premise of the Free Market as the default resource allocation system for human beings, I certainly do not wish to detract away from how the Market Economy has enabled many societies to advance and consume goods and services at previously unattainable levels.

But when proponents of the Free Market make the argument that Free Markets with “necessary and minimal” government intervention is the long-term cure for just about every economic issue imaginable, it is important for us to understand that the Free Market:

- Is a fairly recent social construct, and is definitely not “naturally” occurring to human beings.

- Requires various strong institutional supports, which may make not make it suitable in every society, and also imposes corresponding societal costs.

- Can be complemented, or even substituted with other types of resource allocation systems.

The Free Market is neither “free” in the truest sense, nor is it a natural outcome for societies. Consider two case-in-points where:

- Even in very pro-market societies, theories utilising the price mechanism have not always been able to explain the actual price for various goods and services.

- Even in societies where the Free Market has arguably made them prosperous, there have been protests against it in these societies.

Clearly, the Free Market is not always the best solution for every economic issue. Nonetheless we often hear many voices, even organisations that claim to represent the global masses, that societies should embrace the Free Market as their dominant economic model.

It is therefore important for us to know that the Free Market is neither a truly free one, nor is it natural.

Lend your support!

I hope that you have enjoyed reading this article of mine. I am giving my time to sharing my knowledge and every bit of support means a lot to me! Do drop me a comment or share this article on social media with your friends.

To find out more about my services as a JC Economics tutor, visit my website here.

I wanted to thank you for this excellent read!! I definitely enjoyed every little bit of it. I’ve got you saved as a favorite to check out new things you postÖ

LikeLike

I think this is a real great article.Really thank you! Want more.

LikeLike