As the world experiences inflationary pressures due to a combination of external shocks, recovering post-pandemic demand and supply chain bottlenecks, many central banks have opted for textbook contractionary monetary policies.

Not surprisingly, some countries have opted for a different tack.

Japan had for example, stuck to its guns and maintained its signature ultra-loose monetary policy, to the extent that many Economists consider Japan’s experience to be a sort of real-world Economics experiment, albeit one that has been attempted (and supposedly failed) by others before.

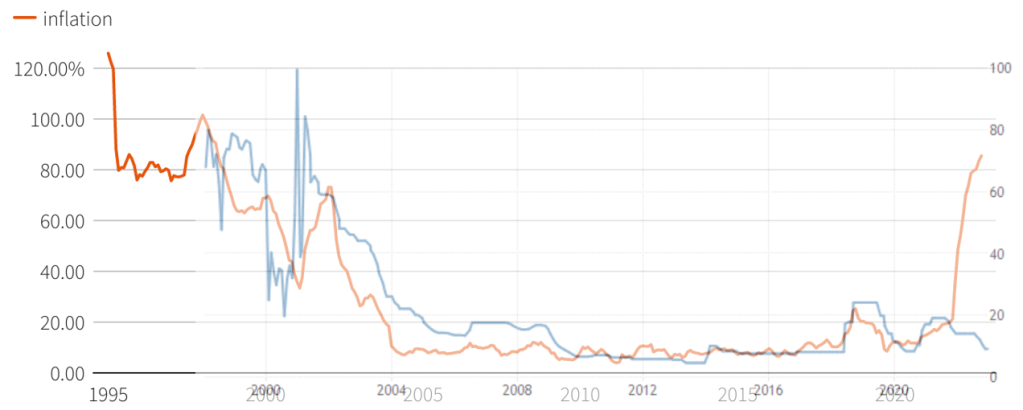

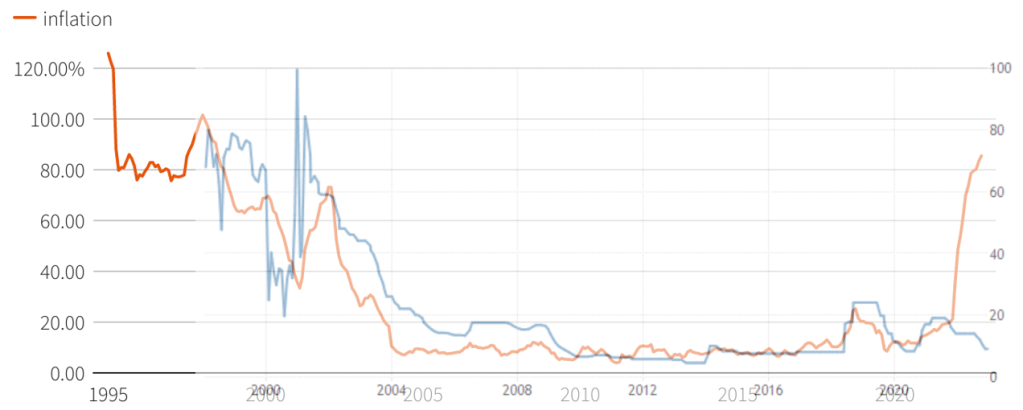

But Turkey has stood out a lot more in recent years, with its unwavering commitment to cut interest rates despite (and/or causing) the dizzying high inflation rate of 85.5% this year:

Below, we have the trend of interest rates over >25 years courtesy of data from the Türkiye Cumhuriyet Merkez Bankası (Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey), compiled by Trading Economics:

We can see that until 2021, there has been a generally observable correlation between interest rate and inflation rate.

In theory, this shouldn’t be surprising – the Turkish Central Bank’s stated mandate is price stability. Therefore textbook monetary policy should see higher interest rates as a response (or even a pre-empt at times) to higher general price levels.

This becomes even more evident when we superimpose both graphs together:

This correlation was rudely interrupted from 2021, when prices soared but interest rates got cut instead. A few observations of Turkish affairs could perhaps glean some insights to this seemingly strange turn of events.

A shift in Central Bank’s mandate?

In recent textbooks, the central bank is supposed to be an independent state apparatus, providing guidance to the economy through fickle political weather with nary a rock to the boat.

In practice, the central bank is still a part of the state – and that means varying lengths of cozying-up or even falling-out between the sitting government and the central bank have been observed across countries, .

Formally, the Turkish Central Bank is an independent entity. However, the President of Turkey has the power to appoint and remove the Central Bank’s governor, which has happened on 4 occasions since 2019.

Sure, there is the Law on the Central Bank of the Republic of Türkiye that spells out the bounds within which such actions may be taken. But such is the hold of power by longtime strongman President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan that he can change the leadership at the Turkish Central Bank, and torpedo any hint of opposition.

Being in control of who heads the Turkish Central Bank, presumably means control over its mandate too.

President Erdoğan will be facing general elections this year and is running on a campaign of economic growth. Incidentally, textbook Economics points to lower interest rate as a monetary tool to achieve this, albeit at the cost of higher inflation rate.

Put 2 and 2 together, and it is hard to avoid the conclusion that, perhaps temporarily at least, the Turkish Central Bank’s mandate has shifted unofficially to one of economic growth instead.

The Lira’s depreciation on steroids.

A side effect to cutting interest rate at a time when others are hiking theirs instead, is a downward pressure on the currency’s value, especially with unfettered flows of capital. Read my previous article about the Impossible Trinity here.

In the case of Turkey, the value of its currency, the Lira, has been commonly described as “crashed”, losing 60% of its value against the USD over the last 2 years:

The Lira’s jump off the proverbial cliff has made life miserable for its citizens through higher import costs, on top of recent global supply shocks from the war between Ukraine and Russia, and recovering post-pandemic demand.

Accordingly though, this was (an unfortunate) part of the plan, by President Erdoğan and the Turkish Central Bank, to reverse Turkey’s current account deficit, by making its exports cheaper internationally.

And it might just about have worked – which really shouldn’t surprise given the extraordinary trade-off suffered by ordinary folks in this economic odyssey. Except that external inflationary pressures have interfered, causing the current account deficit to widen instead. Mamma mia!

When the going gets tough, the tough gets going. That’s the line the Turkish Central Bank is sticking to at least. By that logic, if growth-at-all-cost is what Turkey is aiming for, then the Turks will just have to ride out the current inflationary scourge for a better and more stable future.

To be fair though, economic growth did pick up, reaching 11% in GDP growth in 2021, though slowing to 5% in 2022 despite additional interest rate cuts. This suggests that the Turks may have to suck it up that little longer than what the Turkish Central Bank and President Erdoğan were seemingly letting on.

President Erdoğan’s genuine beliefs.

If the above assertions sounded optimistic given the current misery, I hope it isn’t because of any misguided writing on my part, but rather the very essence of President Erdoğan’s beliefs shining through.

Aside from the beaming optimism that dark inflationary clouds will somehow get dispersed by the holy light that is booming Turkish exports, it appears that President Erdoğan genuinely believes that higher cost-of-living is made worse by higher interest rates, which runs contrary to conventional monetary theory.

By his theory, higher interest rates increase borrowing costs to sellers, which will increase costs of production and cause sellers to pass on additional costs to consumers, ala inflation. You can read more about President Erdoğan’s fascinating formative background here.

This logic, as superficially interpreted, is not the most difficult to believe in the world. Yet there are serious flaws to the argument that beg to be addressed:

- Consumers suffer too, from higher borrowing costs and sellers may not be able to increase their prices easily and still expect to sell;

- The historical trend between Turkish interest rates and general prices do not readily support the hypothesis;

- Turkish business owners, no less, didn’t agree with President Erdoğan’s theory.

It should be mentioned that President Erdoğan’s beliefs hadn’t appeared only now, and have in fact been mentioned several times as far back as 2018, if not earlier. Observers have indeed pointed to President Erdoğan’s convictions being strengthened through the 2010s, when Turkish interest rate cuts hadn’t caused excessive inflationary pressures then:

In fact, this apparently supporting factoid (cutting interest rate doesn’t result in excessive inflation), had a simple-enough explanation that President Erdoğan may have ignored: The 2010s were characterised by anomalously low interest rates around the world, causing Turkey’s relative interest rates to be higher than in absolute terms.

As a result, cutting interest rates at that time hadn’t caused particularly destabilising effects, because the incentives for cross-border capital flows were not so skewed as they are now.

Not recognising this fact has meant that when President Erdoğan insisted on cutting interest rates per his usual experience, at a time when global interest rates started rising, capital flight was almost inevitable, causing the Lira to depreciate rapidly and result in tremendous imported inflation instead.

Invoking (an even) higher authority.

It is unlikely that President Erdoğan would have been so blind as to fail completely in recognising inflation as it swept through the Turkish market.

Since he has to stick to his political guns despite the resulting economic chaos, President Erdoğan has tapped into religious ideology, specifically Islamic proscriptions on usury (charging excess interest as a Sin), to support his case. Especially when the economic realities have been exceptionally painful.

Of course, casting interest rate cuts as an Islamic obligation does more good than harm to President Erdoğan’s religious credentials, which is another key election pitch for the coming general elections.

So whilst President Erdoğan probably sees little reason to question his economic decisions, the question of whether it is indeed the case is moot because the situation now certainly requires him to believe in it to remain convincing (and consistent).

So can cutting interest rate reduce inflation rate?

By now, it should be clear that the answer depends on who you are asking. President Erdoğan seems to (and has to) believe so. My educated guess is that many Turks do not agree, especially the business owners. Yet of course, the political divide is unlikely to yield clear-cut answers.

Economists falling back on conventional wisdom would smack their foreheads and wonder what has become of Turkish economic sense. Yet, some of us will wonder out loud if there is any chance at all, that this curious natural experiment can actually succeed.

Therefore, one is unlikely to get unanimous agreement on whether the Turkish way is an avoidable economic suicide. It will be safe to say though, that few are likely to agree with the Turkish policies completely.

Ultimately, there are many variables, especially external ones, that will engender the Turkish economic story being written for many years to come. And unfortunately for many Turks, the current chapter will be a difficult one, but which the outside world may learn something from reading about it.