Our previous discussion about how governments may produce goods and services took us through direct provisioning as one such method, with real-world examples.

In the IB and “A” level Economics syllabus, another important provisioning strategy by governments is to procure, rather than produce these goods and services, by way of contracting to private firms.

Making a contract.

In its most basic form, when the government is required to procure, rather than produce a good or a service, it goes to a supplier of choice and makes its purchase.

If the government were an individual like you or me, the story might have just started and ended there and then. However, in many countries, especially those with strong institutions, the follow-through from identifying the need for procurement, until the delivery of the good or service, is typically far from straightforward.

In the logical scheme of things, any procurement follows this sequence in general:

- Identify a need;

- Get the price and specifications of the available products in the market;

- Determine the most suitable product to purchase; and finally

- Make the purchase

In the case of most governments, the literal contracting aspect of the purchase comes into play at Step 4, where the supplier becomes the official seller by way of signing an agreement (the Contract). But in fact, the contracting method of government provisioning refers to the entire process as above.

The rational government, by the way, is one assumed to pursue the highest level of social welfare at the least cost.

This simplified overarching maxim is an important guiding light by which we can analyse a government’s provisioning performance and decisions, and is referenced implicitly in evaluating the following advantages and disadvantages of the contracting approach.

Advantages

1. Overcomes gaps in resources or expertise.

Students are inclined to think that governments have superior resources in general and can provision any good or service where required.

That’s wishful thinking.

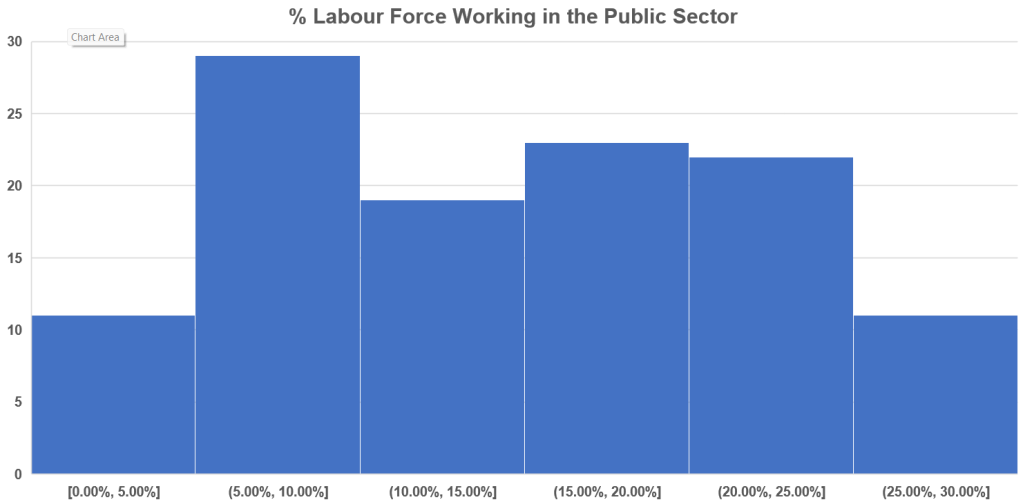

Governments across the world range tremendously in resources and expertise, although the prevailing data suggests that roughly a quarter of governments employ roughly 5-10% of the labour force:

The above histogram plots the number of countries within each public sector size category, as measured by the % of labour force employed from 116 countries, with data from Statista.

In Singapore, there are government fingerprints almost wherever you look, especially when it comes to public amenities, and yet its public sector employs just under 10% of the labour force. This gives some idea that direct provisioning of goods and services, which as a general rule requires more directly-employed labour, is unlikely to be the main mode of government provisioning in Singapore.

Instead, the contracting method is used to overcome capital and labour constraints, especially if government funding is not in fact lacking.

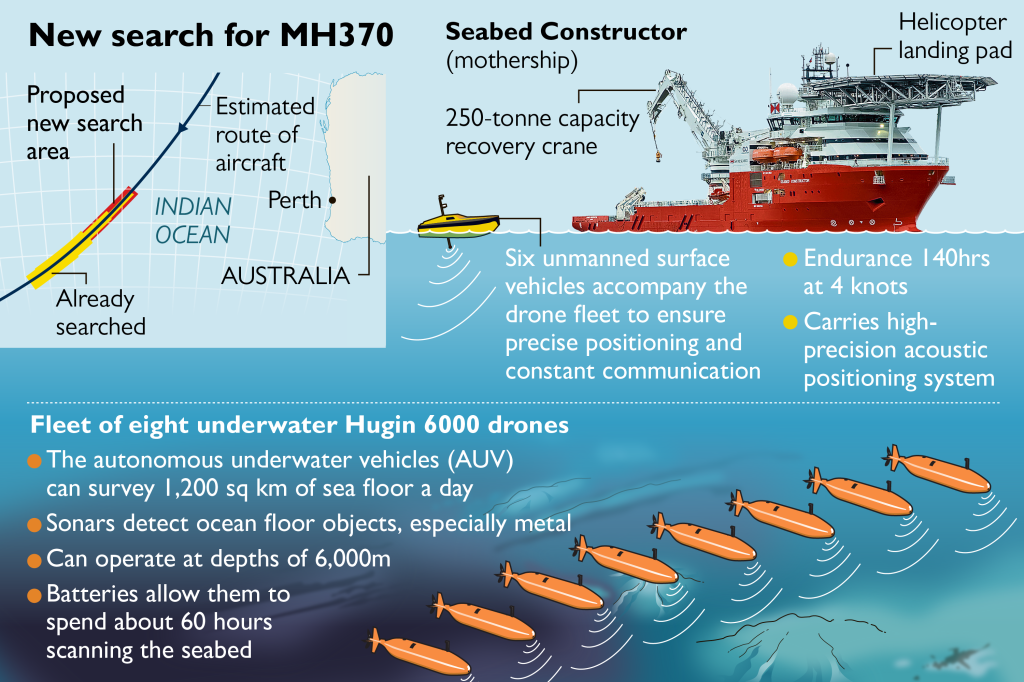

Aside from resource constraints, deep industry-specific knowledge are frequently found with specialists that transcend borders. Extremely challenging examples include the deep-sea search for MH370 contracted to Ocean Infinity by the Malaysian government between in 2018. Such was the confidence of Ocean Infinity in its expertise that the search was contracted on a “no-fee no-find” basis.

2. Speed.

In many cases, procuring goods and services, that are commercially available be it for immediate use or for development, allows for the good or service to be made ready quickly.

A good example was the provisioning of services in vaccinating the Singapore population during the COVID pandemic period, where a tender (the process by which interested sellers can propose solutions for a set of requirements for the buyer to evaluate and contract) was very quickly released for multiple vendors to bid for.

The main purpose of the contracts signed eventually with 17 vendors, was to tap on existing suitable resources in the private sector to urgently assist the public sector in delivering the population’s vaccination. This contracting process took no more than 3 months, highlighting how contract provisioning can be expedient.

3. Competitive price and quality.

The typical assumption in IB and “A” level Economics contend that because governments are not profit-maximising unlike private firms, they do not always have the incentive to be cost efficient and produce better-quality products if they directly provision the goods and services.

A usual litmus test to whether directly provisioned government services are indeed more efficient can be found in privatisation exercises. In Singapore, it is generally agreed that privatising State-Owned Enterprises such as Singtel and Singapore Powers have led to better and more efficient services in the long-run.

By that logic therefore, the contracting method of provisioning should benefit from more efficient operations than a direct provisioning one.

In particular, the tendering process allows for competing bids to be submitted, and the best gets selected by the government to maximise societal surplus (i.e. best quality at lowest price).

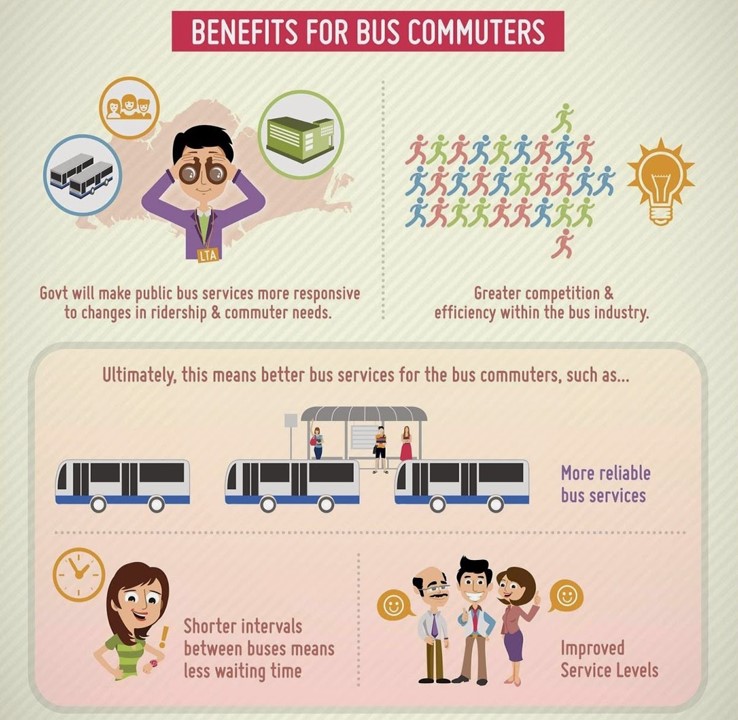

This was the approach taken in reforming the public bus sector in Singapore, in purchasing the assets from the incumbents SBS Transit and SMRT, and then tendering the bus services to the best market participants.

There are dissenting views of course, to whether direct provisioning necessarily leads to inefficient outcomes, and even whether contracting the provisioning to the private sector always leads to better outcomes.

Without going into too much details, whether the contracting method is indeed superior generally rests on:

- The resources, competency and goals of the government; and

- The level of competition in the market (contracting to a monopoly seldom makes for an optimal outcome).

Disadvantages

1. Lack of government ownership.

I have been keeping track of my daily personal expenses since 2017 and one of the side-effects to that has been how I have been able to track my daily events almost to blow-by-blow level.

It struck me then that my expenses have been able to tell a very accurate picture of my life because I rely heavily on purchases to enable my life. What then happens if I can no longer rely on sellers for my day-to-day activities – like during the COVID circuit-breaker period in 2020?

It turns out that a similar concern afflicts governments especially when they rely heavily on the contracting method for provisioning.

Aside from concerns over potential procurement disruption events, relying on contracting key services to private providers tend to stunt the government’s in-house capabilities over the long-term, which carries risk of poor knowledge in these markets.

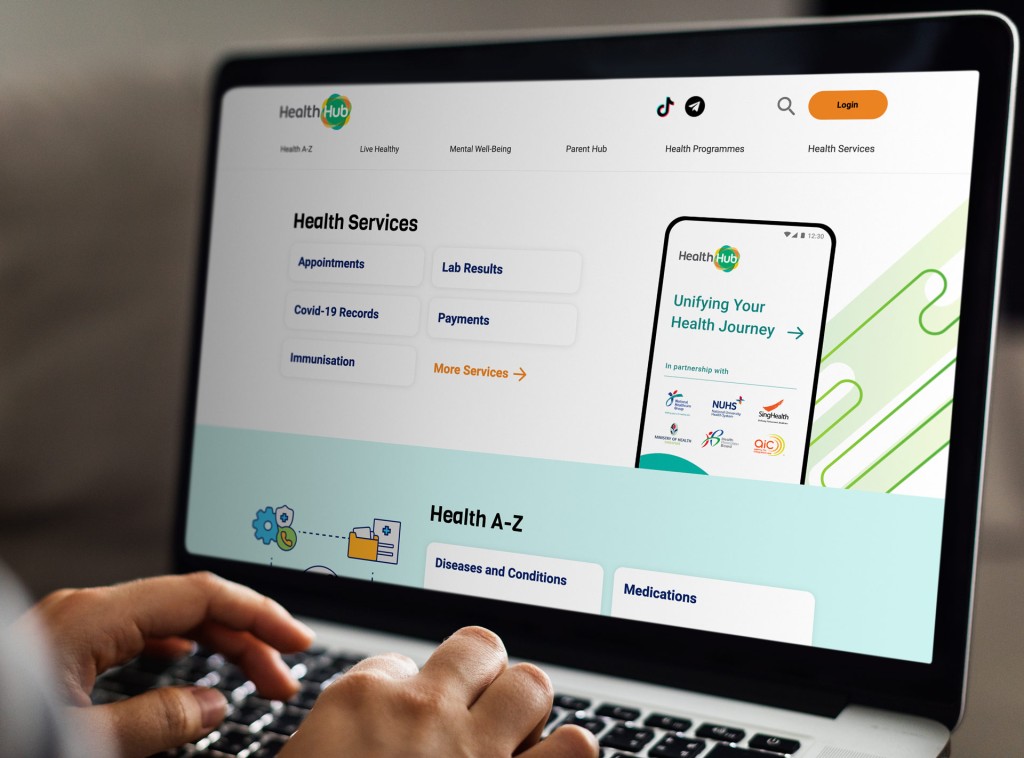

For these reasons, although the Singapore government generally contracts IT solutions to private firms, well-known exceptions exist, such as Singpass and HealthHub – both of which are developed and maintained in-house by their respective government custodians (GovTech and Synapxe).

Such efforts are also in line with the national Smart Nation drive to develop Singapore’s tech-space, which would be harder to achieve if the development of such know-how are done whole-sale by private firms.

2. Contracts can be administrative nightmares.

Contracts are by definition, legally binding documents that require the signatories to comply and fulfill their respective obligations. A major side-effect to this very purpose of a contract includes grotesquely long contracts with as many clauses as the heavens will allow, to try and cover all possibilities.

In the not-too-distant past where the Singapore government administration was still into printing hard-copy contracts for review, yours truly has unwillingly felled many trees and then proceeded to shred documents and return the carbon (to the atmosphere by incineration):

And although it might seem bizarre to the uninitiated, the requirements specified for the good or service to be purchased cannot be too prescriptive as well – to allow flexibility for the private firms’ proposals to yield the best quality the human imagination can allow.

You can start to imagine how many hours the government administrators would have spent:

- Drafting long contracts;

- Arguing internally over the (de)merits of various clauses;

- Negotiating and clarifying the same argued clauses to bewildered vendors;

And god forbid, when either contracting parties supposedly breach the contract clause(s), the legal actions that ensue can often drag…

So in fact, I grossly simplified the above scenarios – they frequently get more complicated and the associated work tends to increase exponentially against them, especially since legalities are involved.

The key point is that the contracting method, whilst supposedly more efficient than direct provisioning in theory, often incurs serious frictional costs that are frequently omitted from the calculation of the “true costs” to the provisioning.

Ironically also, although it is generally held that contracted provisioning, especially for goods and services that are already available in the market, can be faster than direct provisioning, in some extreme cases, the contracted good or service can in fact take very long, perhaps due to requirement or legal complications.

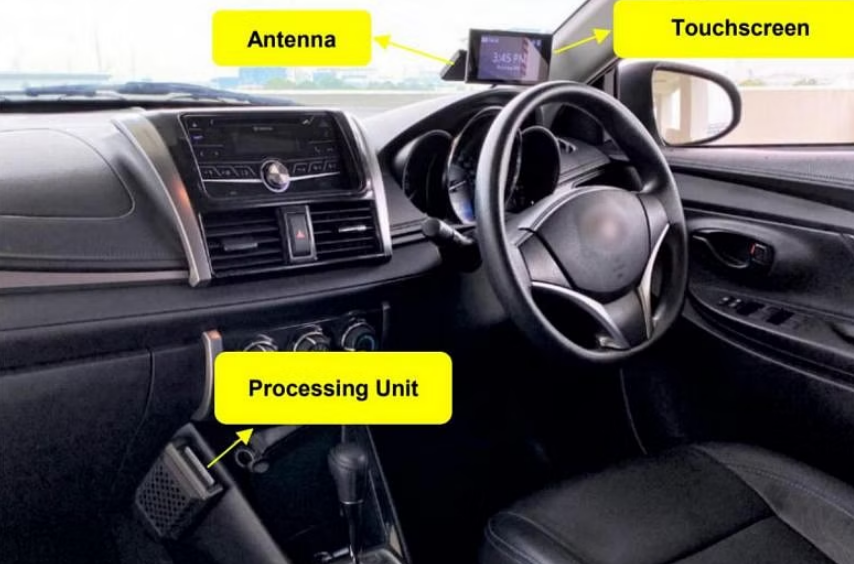

Look no further than Singapore’s Electronic Road Pricing 2.0 project (contracted to the companies, NCS and Mitsubishi Heavy Industries) which began in 2016 and only started rolling out from late 2023. Almost 8 years early!

Granted, it is not entirely clear if a direct provisioning model will work better here since the issue supposedly had to do with locked-in requirements failing to keep up with fast-moving technology. But this should be at least a cautionary tale against wide-eyed optimism for the the contracting method of provisioning.

Concluding Remarks

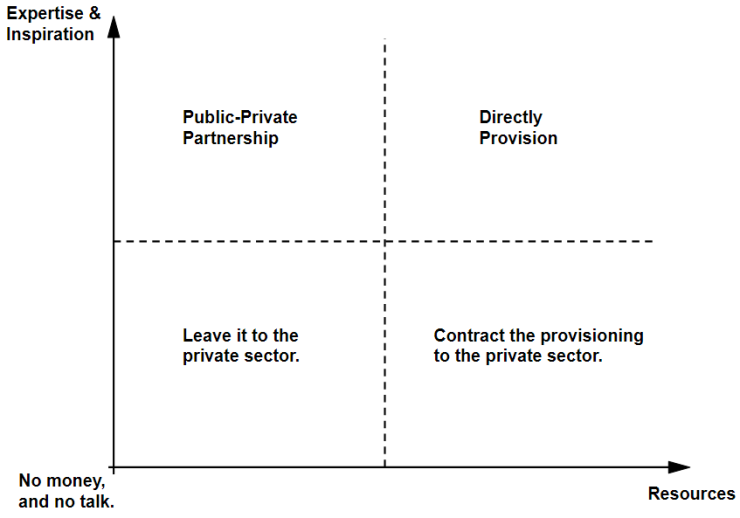

The decision of whether to, and how the government may execute the provisioning of a good or service, may be generalised as so:

The contracting method for provisioning works best for governments that have less-than-concrete execution visions for their needs, and do not need to own the provisioning, but have good budget positions.

Unlike in direct provisioning, the contracting method enables the government to stay lean with flexibility because provisioning contracts are seldom worded for perpetuity. And so if necessary, governments can reduce their provisioning commitments accordingly when required, such as during poor tax revenue years.