As the typical “A Level” and “IB” Economics scriptures go, the market economy can fail to produce enough goods due to various market failures, such as positive externalities, informational failures, and public goods.

Particularly in the case of public goods, where rational producers would not produce anything at all, there is usually a need for governments to participate in the production of the goods and services.

Government production isn’t anything new in the syllabus for “A Level” and “IB” Economics, and students are expected to explain and discuss on such actions by the government, especially in relation to public goods and services.

There are 3 primary ways for the government to produce goods and services:

- Direct Provisioning;

- Contracting; and

- Public-Private Partnerships.

This article delves into these methods of direct government provisioning, which occurs when the government directly delivers goods or services to the public.

Examples in Singapore include:

- Public housing (Housing Development Board)

- Public Education (Ministry Of Education)

- National Defence (The Singapore Armed Forces)

- Public parks (National Parks Board)

A caveat here: The above examples are simplified and do not reflect the complexity in provisioning such goods and services.

For example, the National Defence may, for most purposes, be fronted and manned by the Singapore Armed Forces, but supporting (and crucial) services such as cooking for the personnel are frequently contracted out to private entities.

In reality, as we will see later, the provisioning of goods and services by the government frequently entails combinations of various methods, reflecting the need for peripheral goods and services, as well as the various stages in the supply chain.

Advantages

1. Fair and affordable access is assured.

Because governments are not profit-maximising (benevolence is assumed), the price mechanism is not typically used to such extent as in the free market, or even provided for free.

This eliminates or reduces the issue where people may be unable to access goods and services because they are not able to pay at the market price.

Governments have the capability to go even further, especially if the good or service is scarce, by implementing rationing mechanisms to ensure there is enough to go around for everyone.

Healthcare for example, is critical for all, regardless of socioeconomic status. In some countries therefore, not only is public healthcare directly provisioned by the government, but also free-of-charge, like in the case of the UK’s National Health Service.

In Singapore, public healthcare is not free-of-charge, but heavily and progressively subsidised, with the wealthy receiving less. The healthcare facilities are also distributed across Singapore to ensure good geographical reach to the various population centres.

2. Regulated production and standardisation.

Since the government is producing the good or service, it is able to produce it to the specification that it deems optimal for society, and distribute the same product across society.

In contrast, free markets have a strong tendency towards product differentiation, which encourages market fragmentation, little coordination, and consumer “lock-ins”.

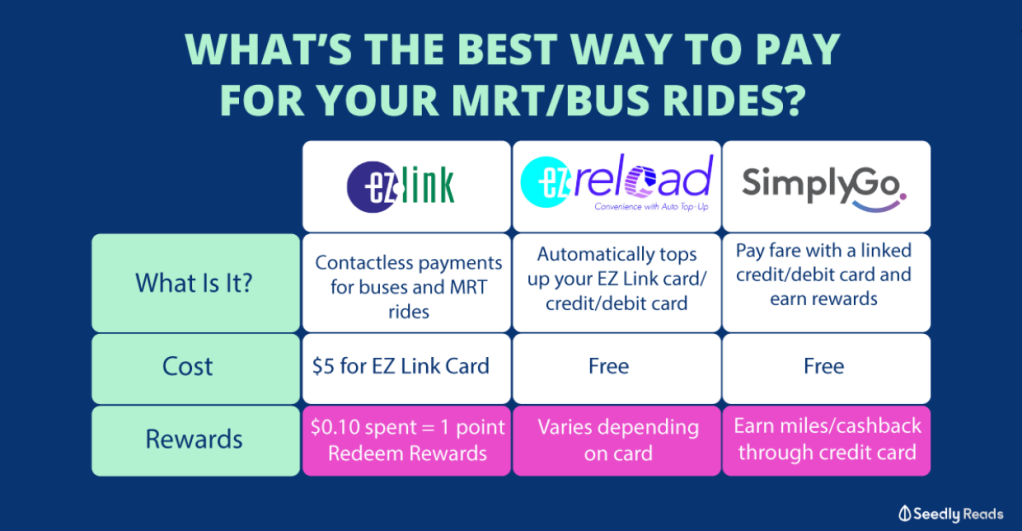

Consider that for all of the boo-hoos over the SimplyGo fiasco, the seeds were sown much earlier with the emergence of competing standards for payments by consumers, resulting in a fragmentation of payment methods available in Singapore.

Inevitably with the need to standardise payment modes on public transport, it was of little surprise to observers that a decision was made to decisively cease the support for Cepas EZ-Link cards.

However, the furious pushback from consumers highlight that in many cases, especially in matters where convenience or safety takes precedence, perhaps a direct provisioning for payment modes to ensure standardisation may have worked better, rather than leaving it to market forces.

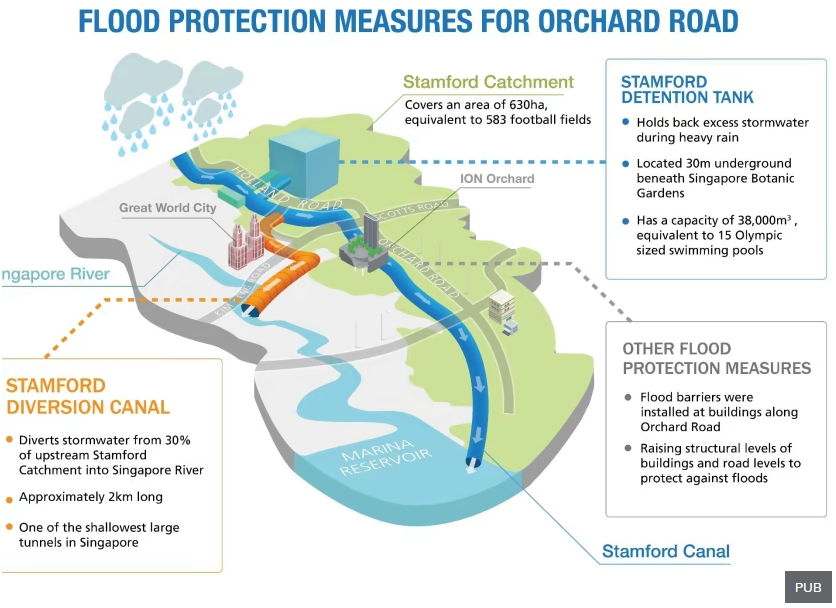

Consider also, the case of flood prevention measures for the latter. Because water indiscriminately flows from higher to lower ground where pathways are available, river and seaside communities with effective floodwater diversionary measures (such as flood walls and levees) often unwittingly result in higher flooding risks and impact to other less-prepared communities.

Large-scale implementation of a flood prevention is therefore crucial, rather than piecemeal private efforts, and best done by the government since it has both the resources and interest in providing societal-wide flood prevention.

Limitations and Disadvantages

1. Difficulties in estimating the optimal price and output.

“A Level” and “IB” Economics students may recall how the first chapter of the textbook or notes mentioned about the command economy and its relative inefficiency in producing goods and services in the optimal amount as compared with the free market’s invisible hand.

Unsurprisingly, because direct provisioning is the command economy in essence, it requires the government to estimate the appropriate price and output, which as you can imagine, can be very difficult, not least because of the diversity in wants and needs of the populace.

Take for example, the direct provisioning of COVID vaccines by Singapore’s health ministry later resulted in under-utilisation of the purchased vaccines, which had to be discarded upon expiry. The value of the “wastage” was estimated to be S$140M.

I am inclined to lean towards the argument that this was a happy problem (since the opposite problem of vaccine shortage would be arguably worse) – but tellingly, the framing of the over-supply as “insurance premium” against the unfolding thread illustrates the “guess-timation” made by the health ministry.

Also, unlike private firms selling the vaccine at a non-zero price which can be lowered to clear the over-supply, the government providing the vaccines at no cost to the public has no recourse because there wasn’t a price mechanism to begin with in allocating vaccines to the public.

2. Limitations in expertise and innovation.

Because governments are not typically profit-maximising, and do not face competition, there is less incentive in producing higher-than-necessary quality products.

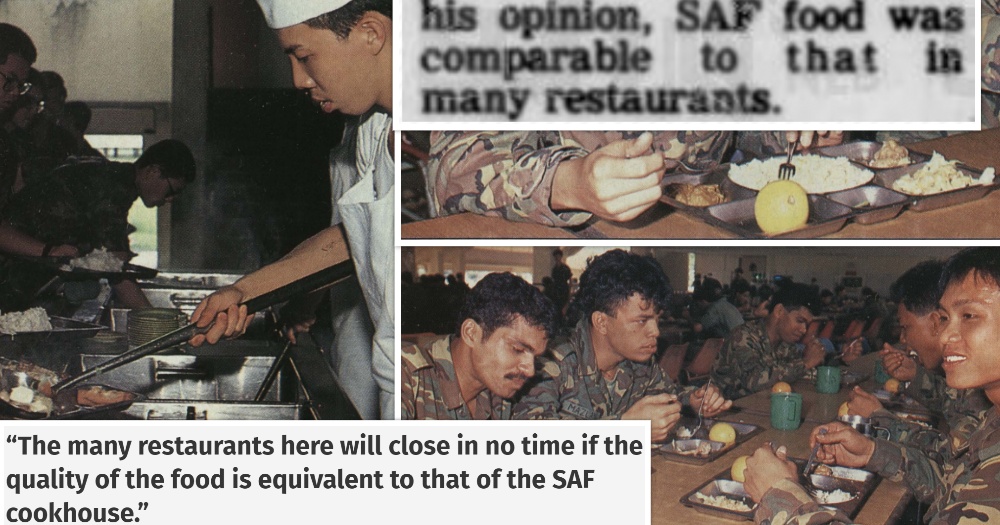

Just ask the older generations about what they thought about the Singapore Army’s fare made from exploiting fellow soldiers to cook in yesteryears…

And compare it with today’s offerings by NTUC Foodfare (an external entity contracted by the Armed Forces):

It may even surprise the younger generation in Singapore to know that many large public-listed “made-in-Singapore” companies were once the Singapore government’s statutory boards. These included Singapore Telecom (today’s Singtel), and the Development Bank of Singapore and the Post Office Savings Bank (both of which formed today’s DBS).

Both companies are still occasionally portrayed as complacent and lacking in innovative spirit. But it pains me to say that I have been in the world long enough to say that they have actually come somewhat far.

Other times, direct provisioning is not even feasible, due to a lack of expertise. It becomes necessary then for the public and private sector to get in bed together to provision the good or service. Spoiler alert: More elaborations to come in the next couple of articles, so we won’t be discussing about them further at this point.

3. High costs to society.

It isn’t surprising that there are many things that governments have to spend on. Singapore’s 2023 National Budget caters S$123B in expected spending, with the largest components being defence, healthcare and education taking nearly 40% of the total share.

I do wonder if it’s also coincidence that the primary services offered by these 3 sectors are directly provisioned by the government. Recall the earlier point about the government’s relative inefficiencies and lack of incentive to reduce costs of production.

Additional direct provisioning of goods and services by the government frequently results in opportunity costs in spending. COVID spending on emergency healthcare provisions in Singapore for example, had diverted resources away from construction projects, such as for public houses and Changi Airport’s expansion.

For all the hubbub on the increase in GST , the increase from 7% to 9% cannot fully cover even the expected increase in healthcare expenditure. Direct provisioning goods and services is therefore seldom a trivial matter to consider.

Concluding Remarks

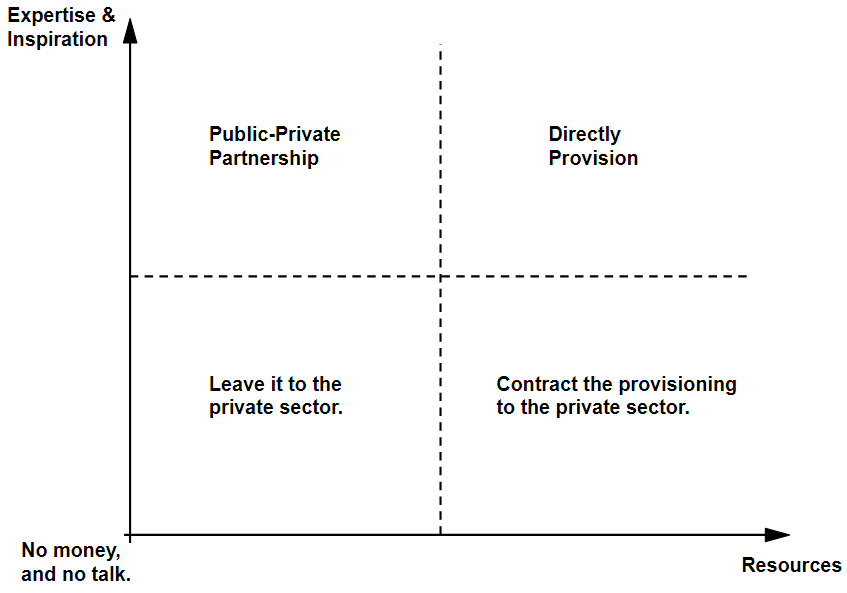

The decision of whether to, and how the government may execute the provisioning of a good or service, may be generalised as so:

Because of the high effort levels and pre-requisites for successful execution, directly provisioning a good or service is not often a default option, especially for budget-prudent governments that prefer to stay lean.

However direct provisioning is best-suited where there is strong need for equitable access, highly regulated and standardised production of goods and services, as well as matters of national exigencies. Provided of course that resources, expertise and inspiration are on hand.

Otherwise, the government may still pursue goods and services provisioning through other means, such as the contracting method as discussed in the next article.